If Live Ain’t Enough for Them: Live Music and an Unexpected Scene in the Last Decade

God save the live music ecosystem

Given the growth of the digital sphere following the COVID-19 pandemic, thinking about live music today is a challenge.[1] However, in live punk music, audiences and venues are not subsidiary but rather essential to maintaining the meaning and importance of this genre and keeping this scene vibrant and alive (Ensminger 2013).[2] At the same time, punk concerts allow participants to abandon their social roles and the systems that establish and maintain these roles. Concert participants immerse themselves in various moments of interrelation and interpenetration with the artists and the bands, promoting a sense of unity and adopting an anti-structure stance.

Simeon Soden states that with the increasing growth of streaming platforms, live music is no longer profitable and is now just a way to promote albums (Soden 2021). In other words, only the most prominent artists have the financial capacity to support live performances. However, we intend to demonstrate that live music still has relevance in the punk universe, even if the events are small in scale. To a certain extent, live music is a means to keep the punk scene alive. Further, contrary to what Soden argues, live music — as opposed to digital — remains a source of economic sustainability for many bands.

Recently, several articles have addressed the issue of live music, but there is almost always an underlying conceptual link with the digital sphere (Lingel and Naaman 2011; Auslander 2012; Zhang and Negus 2021). Our main objective is to analyze the importance of venues that organize live punk music events, as well as to capture their ethos, which is fundamental for the maintenance and activation of the punk scene in Portugal (Barrière 2020). We start from the premise that venues are fundamental to an understanding of the history of punk in Portugal. Returning to David Ensminger’s view that live punk music events focus on logics and dynamics of interrelationship and interpenetration in a scene (Ensminger 2013), it is important to understand the configuration of spaces, cities, and bands in order to gauge the logic of consolidation of punk in Portugal from its beginnings to the present day. In a horizontal sphere of appropriation of sounds, it is through performance that musicians and audiences participate. In this sense, these events enable and encourage a spatial, geographical, economic, and cultural positioning that is the basis for the maintenance of punk.

We adopted a mixed quantitative and qualitative approach to create a relational database of the main punk events organized in Portugal between 2010 and 2015. The following topics are systematized: the cities hosting the events, geographical provenance of the artists, artists’ names, organizing entities, and the type of events. In parallel, we also collected posters from these events, driven by an archival principle of the punk movements in Portugal (Guerra and Alberto 2021; Guerra 2016b). Finally, we made ethnographic observations at some of the punk music events presented in the article.

“Scream with me:” The serendipity of Portuguese live punk music

The importance of live music has been documented from various angles: economic, social, and cultural.[3] However, few studies have focused on live punk music. From any of these angles, there has been a tendency to establish a parallel with festivals, which almost inherently brings into discussion concepts such as the festivalization of culture (Bennett et al. 2014; Guerra 2016a), leading us to associate live music with a global character of great diversity marked by interculturality — the internationalization of audiences and artists. However, we explore how the festivalization of culture serves as a determinant tool for understanding the importance of the venues that organize live punk music events, given that this concept gravitates around a mediation between the global and the local. In fact, the context and the local are among the most important variables in this study (Ensminger 2013).

It is also important to explain that, in our analysis, the “local” variable does not refer to local music in the strict sense of traditional music characteristic of a geographical region, but rather to music or artistic-musical manifestations that legitimate social forms of music in a specific space (Gallan 2012). This legitimation gives rise to the foundations of a range of scenes and subcultures (Bennett 2000). In turn, it is live music that provides coherence to the social function of scenes — in this case, the punk scene — so it is the venues (bars, discos, cinemas, and clubs) that enable the creation of a cultural context (Johnson and Homan 2003).

Live punk music and venues are vital elements in urban cultures (van der Hoeven and Hitters 2019). They bring artists and audiences closer together. Indeed, this is the essence of punk: the rupturing of the barriers between artists and audiences imposed by musical genres such as rock. However, live music has many dimensions. The work of Arno van der Hoeven and Erik Hitters is central to our understanding of the ecology of live music, mainly because they introduce the importance and value of culture into this terminology, especially as it relates to the design of public policies (van der Hoeven and Hitters 2019). Although these conceptions are fundamental, it is not possible to establish a linear relationship with the events under analysis here because underground genres such as punk are not considered in these political conceptions. Thus, an analysis of this kind shows the importance of such practice, given that the movement is still very active in the Portuguese context.

Live music has been the basis of several events aimed at urban dynamization and promotion of social cohesion and inclusion (Holt and Wergin 2013). Simon Frith states that experiencing live music is essential for creating a mythology around specific urban spaces (Frith 2007), which is even more evident in live punk music events. The importance of live music has several aspects, particularly the creation of networks and circuits between venues, artists, managers, and technicians, among others (van der Hoeven and Hitters 2019). These profit-creation and economic sustainability logics are more evident in relation to small venues. Not only is economic sustainability created, but also a common sense of intimacy or belonging is built through the creation of small communities — or communitas (Ensminger 2013) — around the sharing of a particular musical taste and venue.

It is the origin of punk in Portugal upon which its survival depends. Joe-Anne Priel argues that live music plays a decisive role in the creation of individual and collective identities, and in the creation of meaning and emotion towards venues (Priel 2014). Thus, we can affirm that music is a social phenomenon (Swarbrick et al. 2019), which finds its relevance in a dynamic of fruition that can only be activated by live music, as a social connection (Burland and Pitts 2014) between artists, fans, and concert-goers (Leante 2016). Every live performance is idiosyncratic and unpredictable. There is always an innovative element, and expectations are always created around the performance. This is something that doesn’t happen in digital contexts or other musical genres, at least not with the same intensity as live performance (Freeman 2000).

The venues that foster and promote live punk music events are crucial to the creation and maintenance of a mythology around this musical genre. In this way, live punk music assumes a kind of mediation role. Antoine Hennion (1997) and Tia DeNora (2000) are considered primarily responsible for the re-emergence of the study of the relationship between audiences, cultural resources (e.g., music), and daily life in academic work. The concept of mediation offered by Hennion takes us to a place of interrogation that refers to the social world of everyone. Thus, there is a deep relationship between music and society. In live music, both audiences and artists possess the ability to distance their personal identity from their social identity. According to Hennion (1993), music works as a mediation between the individual and their everyday lives (Barrière 2020), with an expressive value (Hennion 1990).

Following Hennion’s concept of mediation, it is important to introduce Simon Frith’s concept of sociology of performance (2007), which establishes the difference between a performance that is learned and one that is felt: “Live performance is taken to be the moment when the music itself speaks most directly to its listeners” (Frith 2007:12). It is closely associated with concepts such as authenticity and a sense of performance, since the lyrics of the songs aim to transmit a message and a political ideology (Guerra 2016b; Guerra 2018; Barros, Capelle and Guerra 2019; Guerra and Menezes 2019).

Methodology

The empirical dimension of this article relied on both quantitative and qualitative based methods. We highlight the ethnographic studies carried out; specifically, the observation of about thirty live punk music events in Portugal, in several cities such as Porto, Lisbon, and Coimbra. We wanted to deepen the various fields of performance of the punk universe. We also questioned whether live punk music still existed in Portugal, given that several people mentioned that punk was “dead” or asleep. We did not take this to be true; we believed that punk continued from the 1980s and 1990s.

We had just two hypotheses: either punk was no longer present as a musical genre present in Portugal, or it was. We adopted a quantitative methodology to construct a relational database appealing to the secondary production of data. Event agendas were consulted, and the punk events disclosed. We also consulted websites and social networks — sources of information provided by the social agents participating in the punk live music scene — as the basis for the dissemination of these events. For this purpose, we sought to systematically collect, identify, and categorize all the live punk music events we could find on the web between 2010 and 2015. This analysis focuses on about 680 events in Portugal. Because many events have an informal or underground nature, we used a “snowball method” (Baltar and Brunet 2011). We contacted some key actors via social networks and used previous contacts with venues which promoted punk concerts; through them, we found other venues and other initiatives.

Portugal is still marked by a weakness regarding statistical information about the cultural sector (Guerra 2017). In analytical terms, we first created categories linked to the memory of the event (including the name and the date of the event, as well as collected and catalogued posters for each event); second, we created categories related to consumption and artistic programming (all the bands that participated in the events, their country of origin, and links to social networks); third, we identified the venues where the events took place (bars or cinemas, or locations with dance space); and fourth, we geo-referenced each venue, identifying their municipality, county, and district in order to understand the cultural activity. Our main goal was to understand the activity of live punk events in Portugal, by region and by type of venue, in a longitudinal logic.

Seeing is believing: Punk is still alive

Live punk music has only recently acquired attention from academics (Holt 2010). A few studies have been done in the field of sociology, but these are directed more towards festivals (Guerra 2019). This article focuses on the role of live punk music in the configuration and maintenance of a scene and how it shapes the ways in which this genre is transmitted and received by the audiences. In other words, we intend to understand how the organization of these punk live music events is constituted as the means of maintaining the authenticity of the scene. This is because it is a musical genre that does not live on pre-recordings, but rather feeds on face-to-face interactions with audiences. This study deals with live music in physical venues, and it seeks to identify the bands, the venues, and the aesthetics associated with them, aiming to demonstrate that the punk movement does not depend on the digital sphere to stay alive. Punk remains faithful to its genesis, strongly anchored in the social and collective experience of live music. In fact, punk can be understood as a reflexive (sub)culture, the functional role of which is to exist outside mainstream culture, through participation in and organization of these events (Frith 1997).

Indeed, while constructing our survey, we noticed that research was still somewhat lacking regarding these topics. There was interest in technologies, such as social media, and their connection with performance, as well as in genres such as pop. However, for the two themes we propose here, the theoretical void remains. The work developed by Philip Auslander has drawn attention to live performance (Auslander 1999). However, according to Holt, “scholars have not yet explored in detail what is implied when a concert or a DJ set is identified as live music and how that informs cultural practice” (2010:244). Live punk music is produced in the context of several social transformations, which confer new meanings.

Initially, live music was linked to commerce, media, and entertainment — elements from which punk wanted to move away and even counteract. Nevertheless, it now seems that these categories have become innocuous in describing the role and impacts of live music. No empirical work is necessary to say that live music is cathartic and that it brings a feeling of individual and collective liberation. Haven’t we all sighed with nostalgia when remembering a concert? Take the example of the 1976 Sex Pistols concert, often regarded as changing the history of punk forever (Inglis 2006).[4] In this sense, we assess that live punk music has an aura (Benjamin 1994), understood in a broader sense of communication. It is not bound to a recording or a presence in mainstream media. Punk music has a strong social and historical dimension. However, as Holt (2011) mentions, live music is also commonly used to advertise venues, which is confirmed by our analysis.

Our intention was to understand the the connection between punk music and its historical and social contexts in the years between 2010 and 2015. How could such a relationship manifest itself? Portugal was heavily impacted by the 2008 global financial crisis, resulting in the Portuguese financial crisis, which manifested between 2010 and 2014, almost exactly covering our period of analysis. This was a very troubled period in Portugal’s political and economic history, when many support systems were cut, the unemployment rate rose, and austerity was the norm (Feixa and Nofre 2013; Silva, Guerra, and Santos 2018). During this period, several artists used music to both denounce and confront the crisis (Guerra 2020), but few studies focused on other forms of subversion and resistance beyond lyrics and musical production.

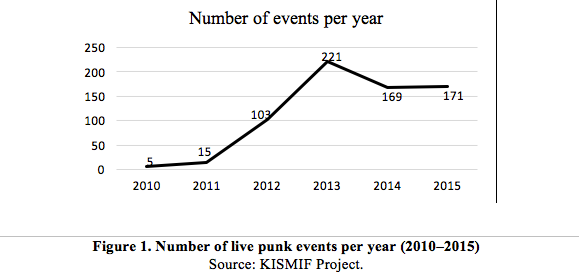

As Figure 1 shows, in 2010, when the financial crisis began, the number of events was small (only five). However, in 2011, there was an increase (fifteen events), boosted in 2013, when two hundred twenty-one events were held throughout the country, while the crisis was still very present. The financial assistance program requested by Portugal ended in 2014, with the country having complied with the three-year plan. Although there had been some economic improvements, poverty levels and unemployment rates were high; consequently, many families depended on monetary support such as RSI (Social Insertion Income). Because of this, one would expect participation in and organization of punk concerts to be sparse for economic reasons since establishments suffered greatly from the economic crisis. Yet live punk music was important as a way of resisting the economic, political, and social conditions of the time, especially concerts such as those of Crise Total [Total Crisis], the first Portuguese anarcho-punk band. In 2013, we highlighted events such as Colhões de Ferro VIII (concert), Lodo Punk na Spreita (concert) (see Figure 2), Noite de PUNK & Roll (DJ set), and Punk Rock Até Aos Ossos (concert/cinema).

Another conclusion drawn from the data presented in Figure 1 relates to live punk music as a motivational factor for the subsistence of the venues — particularly through consumption during the events, since most have minimal or no entrance fees. These events were (and are) oriented by a marketing and audience loyalty logic — not only to the venues, but also to the bands. Concerts are the main source of income for these bands (Frith 2007), which for the most part operate according to a DIY logic (Lingel and Naaman 2012).

As punk and some sub-genres, such as straight edge, involve supporting various political causes, part of the entrance fee often went to said causes.[5] Live music was therefore a driving force for local causes. Most events (around four hundred ninety) happened in the summer months — between June and September — which is a transversal characteristic for all musical genres; in this sense, music in general acquires an extra connotation in terms of entertainment, fruition, and leisure logics. Most festivals also take place in the summer months. Outdoor activities were more frequent at this time, while the rest of the year saw smaller indoor initiatives in bars or discos. This enables us to understand that live punk music events tend to follow the same programming logic as other mainstream events or commercial music genres, despite not being subject to the same kind of publicity and thus diverging from the superficiality of postmodernism (Moore 2004).

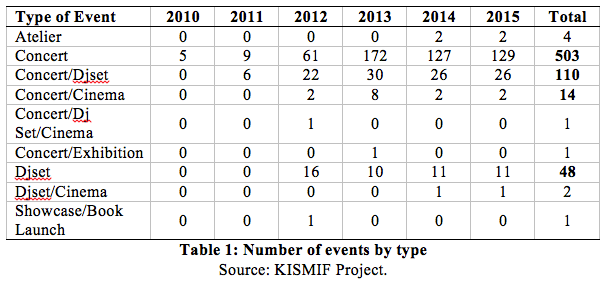

The continuity and frequency of live music events at the core of punk in Portugal shows it is possible for this musical genre to allow individuals to share common ground, accentuating feelings of belonging to a community or a scene (Guerra 2014). This systematicity of events shows the creation of group identities mapped by the relationships between individuals attending the events, but also with the organizers. We can see a quick and systematic dynamization of the punk movement, demonstrating that these events build links between individuals and the subculture. The kinds of events being discussed are shown in Table 1.

Unsurprisingly, concerts are the predominant type of event (five hundred three concerts), followed by concerts accompanied by a DJ set (one hundred-ten events) or even just the DJ set (forty-eight events), which are intrinsically associated with smaller venues such as bars. DJ sets are important because they show the adaptability of punk music and events of this nature to contemporaneity, something that did not occur in the early days of the punk scene in Portugal. Once again, we establish a parallel with the DIY ethos, which is based on adaptability to the demands and changes of social contexts, as a way of maintenance and participation within a scene. However, the presence of events combining the typology of concerts and cinema is noteworthy, with around fourteen events identified. Examples include Hello Winter Fest, TUGA Straight Edge Day (Figure 4), Prostitour and Alenquer Rocks. With this said, we cannot fail to equate a certain evolution of punk with these events (Guerra 2013). It is no longer merely associated with bands and phonographic records, but has expanded to other formats, denoting the emergence of a certain stylistic hybridism. This combination and evolution offer singularity to the Portuguese punk scene: it has not stagnated or resigned itself to the formats of the 1970s or 1980s, remaining dynamic and persistent in defence of the underground, even if the initiatives are sporadic. Around ninety-five percent of the events last just one day, and around four percent only two days.

The Metamorphosis of Chameleonic Punk

Pipe considers that live music should be taken as a multimodal experience in which visual components play a key role (Pipe 2018). In the case of punk, the visual component may be more important, as it also gives meaning to the different musical subgenres that fall within punk. In parallel, the question of corporality, as a form of communication of the musical genre and its acceptance, is very present in these concerts (Longhurst 2007). In this sense, the bands also assume a prominent role. In our analysis, we verified that most events have a multifaceted program. Around seventy percent have a lineup of two to five bands, with only seventeen percent having the performance of one band. Another interesting aspect lies in the fact that the event name contains the bands performing, examples of which are Rebels in Packages + Piss!! + Leather + Superflares (2015), Monarch + Teething + Atentado + DDMC + Oniromant (2015), Stick to Your Guns + Backflip + Brace Yourself + Dear Watson (2014), and o XIBALBA + HIEROPHANT + Steal Your Crown + Utopium (2013).

Bands also have a decisive role in keeping this scene alive. Thus, while we were in the process of analyzing and categorizing the data, we considered it important to understand the role of bands in these dynamics. Having established that the punk movement was marked by a certain hybridism, we tried to understand whether the bands in these line-ups were all Portuguese or not. Then, we proceeded to collect and quantify the bands that appeared most frequently. We concluded that those bands that appeared most frequently were Challenge (Figure 6) (thirty events), Dalai Lume (Figure 7) (twenty-eight events), Re-censurados (Figure 7) (twenty-five events), Shitmouth (Figure 6) (twenty-seven events) and The Parkinsons (twenty-nine events).

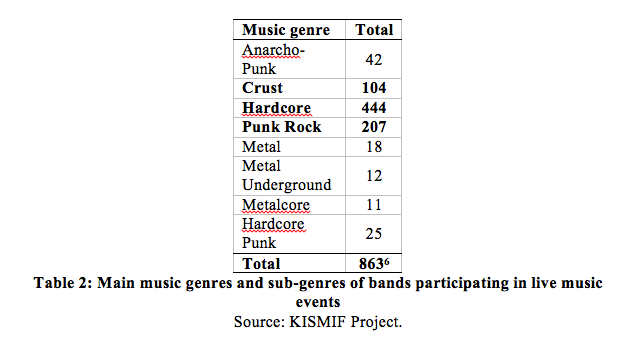

More important than knowing which bands participate more assiduously in these events is understanding the main musical genres and sub-genres assumed to be determinant (Table 2).

It is not surprising that punk rock has a strong presence in these live music events. Punk rock and punk are intimately linked to logics and processes of resistance, showing that live music events are one more iteration of these same processes and logics of individual and collective affirmation, but also of claim and denunciation (Guerra 2014). In parallel, the strong presence of hardcore deserves to be highlighted. Both these musical genres are marked by physicality and even violence. Discussions of resistance almost inevitably center white, heterosexual, and mostly male individuals. These issues have been considered by authors such as Sharp and Nilan (2014; 2017), Montoro-Pons, Cuadrado-Garcia, and Casasu-Estelles (2013), who point out that men more frequently attend live music events. From our personal experience, we gauged that attendees of heavy metal events in the city of Porto, in venues such as the Metalpoint, were predominantly male.[6]

By listing the genres presented above as those with the greatest representation in the data and building on empirical knowledge from previous research, we can conclude that attending live punk music events is not only linked to the musical genre itself, or even to the bands.[7] The motivations for attending should be analyzed in a similar way to the musical genre (Brown and Knox 2017). Thinking about these music scenes, we can infer that experiencing music and individuals’ feelings of being part of a movement are among the main reasons. This is more evident when we look at events with an underground character. Further, the physical structure of some venues, such as their small size, can enhance the connection with the bands, creating a relationship of proximity, friendship, and sharing, and influencing the use of these venues. Another characteristic is the visual aspect of the performances, and the affective feelings that are created in relation to the memorabilia surrounding them (merchandising, CDs, tickets, etc.). Thus, the physical dimensions of music and of individual and collective expression are very much present (Pitts 2014).

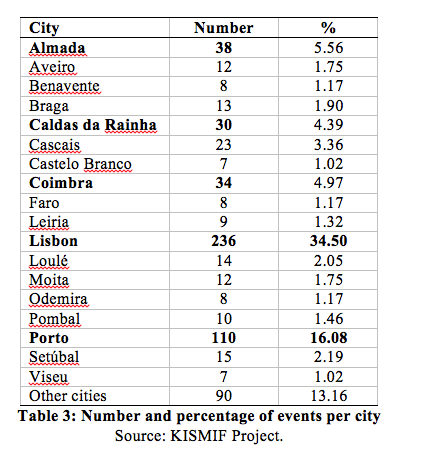

It is evident that live music, the motivations that may underlie the attendance of these events, and the musical genre itself are fundamental to some of the reasons why these underground events remain. However, we cannot ignore the double-edged relationship between geographical space and events. Table 3 shows the main cities that hosted the most live punk music events.

Portugal remains macro-centric in the artistic and cultural field, with the cities of Porto (one hundred ten events) and Lisbon (two hundred thirty-six events) continuing to be hubs for artistic production and consumption. Beyond the obvious characteristics of political power and the centralization of economic investment, this can be explained by the fact that culture — particularly music — has long been considered as a form of social revaluation of cities (Guerra, Bittencourt, and Domingues 2018). Since they have the necessary infrastructure, these large metropolises have become mediators of cultural dynamics. Despite belonging to the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon (AML), places such as Almada — where thirty events were counted — fit under the narrative of the development of new spaces of consumption, social recomposition, and development of a cultural economy (Guerra, Bittencourt, and Domingues 2018), embodying a change in the urban landscape within the scope of post-modern processes of urban development.

The preponderance of events in these cities does not surprise us. Guerra and Bennett have already listed them, associating them with a clear idea of “where there are people, there are young people” (2020:74), thus establishing a connection with the genres and subgenres of punk, and highlighting cities such as Lisbon, Porto, Loures, Cascais (twenty-three events), and Almada as leading this genre. Then come medium-sized cities such as Viana do Castelo, Braga (thirteen events), Aveiro (twelve events), Coimbra (thirty-four events), Setúbal (fifteen events), and Faro (eight events). Also of note are the small cities inside the country, such as Viseu, Castelo Branco (seven events), Caldas da Rainha (thirty events), and Loulé (fourteen events). Thus, despite being considered small or medium-sized, cities such as Coimbra, Caldas da Rainha, Setúbal, and Loulé report a high number of live events. Moreover, because there are few physical venues for events, a community forms around the local scene (Guerra and Bennett 2020), with a shared motivation to attend these events (Brown and Knox 2017). This idea of community has been established since the early 1980s, when Portugal reopened to the world after the end of the Salazar military dictatorship, since most of these medium and small cities witnessed a Portuguese rock boom, with the emergence of bands, venues, and stages (Rendell 2021).

Many of these cities already had a connection to the arts, which would have acted as an incendiary fuse for the explosion and consolidation of the punk movement and subsequent subgenres. However, there is insufficient space for that topic here. Having highlighted the main cities hosting live music events of this nature, we can see which cities stand out for the lineups of their punk events, to understand their origin and verify whether these cities also stand out for the “production” and “expedition” of artists to the rest of the country.

The years 2013, 2014, and 2015 were landmarks for the affirmation of the punk scene in live music events. They saw the largest participation of artists. If there is a relationship between the year and the number of events held, it is clear that the city of origin of the bands also plays a prominent role. Therefore, from 2013 to 2015, Porto and Lisbon were the main cities of origin of the bands that comprised these events. In the case of Porto, between 2013 and 2015 we counted the presence of about one hundred twenty-eight bands. In Lisbon, we counted about three hundred, a substantially higher number that corroborates what Guerra, Bittencourt, and Domingues (2018) refer to as driving forces of urban and social recomposition in artistic and cultural production. Examples of bands from Porto are Cruelist, Fina Flor do Entulho (Figure 8), and Erro Crasso. In the case of Lisbon, we highlight bands such as A Life to Take, Crepúsculo Maldito, and Gatos Pingados (Figure 9). For the events in the year 2013, we verified the presence of nine bands originating from Almada, fourteen from Caldas da Rainha, and eleven from Coimbra. Cities such as Leiria and Guimarães have also taken on greater importance in recent years, particularly in 2015, with eight and seven bands respectively originating from them. In 2010, neither city had a band participating in these events.

Another interesting aspect of this scene is the impact of foreign cities — some of them geographically close to Portugal —on the Portuguese punk scene. The majority of international bands in Portugal came from France (twelve bands), followed by the Netherlands (seven bands), Norway (five bands), the United States (five bands), Spain (five bands), and Germany (four bands). We cannot neglect the work of Gallan on what is considered as being “local” (Gallan 2012) — in order to portray a local scene, as we have tried to do, it is necessary to consider the people, the organizations, the events, and the situations associated with the consumptions of a shared style of music. Thus, given the strong symbiosis between national and international artists in these live music events, we can affirm the global and local character of the music industry (Bennett and Peterson 2004).

Conclusion: After all, punk lives through live music

This article has demonstrated that it is possible to verify that the punk scene is still very much active and alive in Portugal, especially in the organization of live music events. The COVID-19 pandemic has put a brake on the growth and organization of these events and brought numerous challenges to the music industry and artists. However, live punk music materializes geographical locations and territories and vernacular cultures (Gallan 2012). Furthermore, live music events are strongly linked to the strength of the musical genres in the spaces where they are staged. There is a historical connection of punk with cities such as Lisbon, Coimbra, and Castelo Branco. Guerra (2018) points out that the autonomy of the punk scene is due to practices such as DIY, but it is also due to the venues that organize these events, in the sense that they have strong relationships of proximity with the actors in the scene: the artists and audiences (Barrière 2020).

This article is intended to contribute academically to the development of the field of studies focused on the importance of live music, as well as at the level of theorization around the concept of scene and subculture (Bennett 2000). It demonstrates how live music events foster the social function of punk music in Portugal, giving rise to the construction of a cultural context that is tendentially forgotten or considered superfluous (Johnson and Homan 2003). We conclude that places — namely cities and venues — are crucial to the creation and maintenance of a scene around a given musical genre, which is especially evident in the case of punk. In fact, it is these elements that have been at the root of the punk movement in Portugal and its maintenance and survival since the early 1970s. At the same time, we demonstrated that live punk music events transform the atmosphere of the places they occupy, which in turn reinforces the argument that music assumes a mediating character (Hennion 1997). This was evidenced by the data regarding the relationship between the number of live music events and their coincidence with the periods of strong economic and financial crisis that deeply affected Portugal.

Acknowledgment

This article was supported by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology within the scope of UIDB/00727/2020. We very much appreciate the help of Ana Oliveira, Hugo Ferro, Sofia Sousa, and Tânia Moreira in the process of data gathering and analysis.

References

Auslander, Philip. 1999. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. London: Routledge.

------. 2012. “Digital Liveness: A Historic-philosophical Perspective.” PAJ Journal of Performance and Art 34(3):3–11.

Baltar, Fabiola and Ignasi Brunet. 2012. “Social Research 2.0: Virtual Snowball Sampling Method Using Facebook.” Internet Research 22(1):57–74.

Barrière, Louise. 2020. “Safer Spaces for Everyone? The Ladyfest Scene as an Innovative Field for the Fight Against Gendered Violence in the Live Music Industry.” Arts & the Market 11(2):61–75.

Barros, Leandro Eduardo Vieira, Mônica Carvalho Alves Capelle and Paula Guerra. 2019. “Symbolic Interactionism and Career Outsider: A Theoretical Perspective for Career Study.” REAd – Revista Eletrônica de Administração 25(1):26–48.

Benjamin, Walter. 1994. A obra de arte na era de sua reprodutibilidade técnica. Obras escolhidas: Magia e técnica, arte e política. São Paulo: Brasiliense.

Bennett, Andy. 2000. Popular Music and Youth Culture: Music Identity and Place. New York: Palgrave.

Bennett, Andy, Jodie Taylor and Ian Woodward. 2014. The Festivalization of Culture. Farnham: Ashgate.

Bennett, Andy and Richard Peterson. 2004. Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Brown, Steven Caldwell and Don Knox. 2017. “Why Go to Pop Concerts? The Motivations Behind Live Music Attendance.” Musicae Scientiae 21(3):233–249.

Burland, Karen and Stephanie Pitts. 2014. Coughing and Clapping: Investigating the Audience Experience. New York: Routledge.

DeNora, Tia. 2000. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ensminger, David. 2013. “Slamdance in the No Time Zone: Punk as Repertoire for Liminality.” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 9(3):1–13.

Feixa, Carles and Jordi Nofre. 2013. #GeneraciónIndignada. Topías y utopías del 15M [#GeneraciónIndignada. Topias and Utopias of the 15M]. Lleida: Milenio Publicaciones.

Freeman, Walter J. 2000. “A Neurobiological Role of Music in Social Bonding.” In The Origins of Music, edited by Nills Wallin, Björn Merkur and Steven Brown, 411 –424. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Frith, Simon. 2007. “Live Music Matters.” Scottish Music Review 1(1):1–17.

Gallan, Ben. 2012. “Gatekeeping Night Spaces: The Role of Booking Agents in Creating ‘Local’ Live Music Venues and Scenes.” Australian Geographer 43(1):35–50.

------. 2020. “The Song is Still a ‘Weapon’: The Portuguese Identity in Times of Crises.” Young 28(1):14–31.

------. 2019. “Espaços liminares de sociabilidade contemporânea. O caso ilustrativo do Festival Paredes de Coura, Portugal.” Estudos de Sociologia 2(25):51–88.

------. 2018. “Raw Power: Punk, DIY and Underground Cultures as Spaces of Resistance in Contemporary Portugal.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):241–259.

------. 2017. “‘Just Can’t Go to Sleep:’ DIY Cultures and Alternative Economies Facing Social Theory.” Portuguese Journal of Social Sciences 16(3):283–303.

------. 2016a. “‘From the Night and the Light, All Festivals are Golden:’ The Festivalization of Culture in the Late Modernity.” In Redefining Art Worlds in the Late Modernity, edited by Paula Guerra and Pedro Costa, 39–67. Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

------. 2016b. “Keep It Rocking: The Social Space of Portuguese Alternative Rock (1980–2010).” Journal of Sociology 52(4):615–630.

Guerra, Paula. 2014. “Punk, Expectations, Breaches and Metamorphoses: Portugal, 1977–2012.” Critical Arts 28(1):111–122.

Guerra, Paula and Thiago Pereira Alberto. 2021. “Welcome to the ‘Modern Age:’ The Imagery of Punk from the 1970s in the Redefinition of the New York Music Scene of the 2000s and Beyond.” In Trans-Global Punk Scenes: The Punk Reader Volume 2, edited by Russ Bestley, Mike Dines, Paula Guerra and Alastair Gordon, 162–178. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Guerra, Paula and Andy Bennett. 2020. “Punk Portugal, 1977–2012: A Preliminary Genealogy.” Popular Music History 13(3):215–234.

Guerra, Paula and Pedro Menezes. 2019. “Dias de insurreição em busca do sublime: as cenas punk portuguesas e brasileiras.” Sociedade e Estado 34(2):485–512.

Guerra, Paula, Luiza Bittencourt and Daniel Domingues. 2018. “Sons do Porto: para uma cartografia sónica da cidade vivida.” Cuadernos de etnomusicologia 12:184–210.

Hennion, Antoine. 1997. “Baroque and Rock: Music, Mediators and Musical Taste.” Poetics 24:415–435.

Hennion, Antoine. 1993. La passion musicale. Une sociologie de la mediation. Paris: Édition Métailié.

Holt, Fabian. 2010. “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13(2):243–261.

Holt, Fabian and Carsten Wergin. 2013. “Introduction: Musical Performance and the Changing City.” In Musical Performance and the Changing City: Post-industrial Contexts in Europe and the United States, edited by Fabian Holt and Carsten Wergin 1–24. New York: Routledge.

Johnson, Bruce and Shane Homan. 2003. Vanishing Acts: An Inquiry into the State of Live Popular Music Opportunities in NSW. Sydney: Australia Council.

Leante, Laura. 2016. “Observing Musicians/Audience Interaction in North Indian Classical Music Performance.” In Musicians and Their Audiences: Performance, Speech, and Mediation, edited by Ionnis Tsioulakis and Elina Hytönen-Ng, 50–65. New York: Routledge.

Lingel, Jessa and Mor Naama. 2011. “‘You Should Have Been There, Man:’ Live Music, DIY Content and Online Communities.” New Media & Society 14(2):332–349.

Longhurst, Brian. 2007. Popular Music and Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Montoro-Pons, Juan., Manuel Cuadrado-Garcia and Trinidad Casasus-Estelles. 2013. “Analysing the Popular Music Audience: Determinants of Participation and Frequency of Attendance.” International Journal of Music Business Research 2(1):35–62.

Moore, Ryan. 2004. “Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction.” The Communication Review 7(3):305–327.

Pipe, Liz. 2018. The Role of Gesture and Non-verbal Communication in Popular Music Performance, and Its Application to Curriculum and Pedagogy. PhD thesis, University of West London.

Pitts, Stephanie. 2014. “Musical, Social and Moral Dilemmas: Investigating Audience Motivations to Attend Concerts.” In Coughing and Clapping: Investigating Audience Experience, edited by Karen Burland and Stephanie Pitts, 21–34. Farnham: Ashgate.

Priel, Joe-Anne. 2014. Hamilton Music Strategy Report. Hamilton: Tourism and Culture Division of the City of Hamilton, https://www.hamilton.ca/city-initiativesstrategies-actions/hamilton-music-strategy

Rendell, James. 2021. “Staying In, Rocking Out: Online Live Music Portal Shows During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Convergence 27(4):1092–1111.

Sharp, Megan and Pam Nilan. 2015. “Queer Punch: Young Women in the Newcastle Hardcore Space.” Journal of Youth Studies 18(4):451-467.

Sharp, Megan and Pam Nilan. 2017. “Floorgasm: Queer(s), Solidarity and Resilience in Punk”. Emotion, Space and Society 25:71–78.

Silva, Augusto Santos and Paula Guerra. 2015. As palavras do punk. Lisboa: Alêtheia.

Silva, Augusto Santos, Paula Guerra and Helena Silva 2018. “When Art Meets Crisis: The Portuguese Story and Beyond.” Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 86:27–43.

Soden, Simeon. 2021. PayPal for Punks: Blockchain for DIY music. PhD thesis, University of Sunderland.

Swarbrick, Dana, Dan Bosnyak, Livingstone, Steven, Jotthi Bansal, Susan Marsh-Rollo, Matthew Woolhouse and Laurel Trainor. 2019. “How Live Music Moves Us: Head Movement Differences in Audiences to Live Versus Recorded Music.” Frontiers in Psychology 9:1–11.

van der Hoeven, Arno and Erik Hitters. 2019. “The Social and Cultural Value of Live Music: Sustaining Urban Live Music Ecologies.” Cities 90:263–271.

Zhang, Qian and Keith Negus. 2021. “Stages, Platforms, Streams: The Economies and Industries of Live Music after Digitalization.” Popular Music and Society.

Notes

[1] Section title inspired by the song “God Save The Queen” by Sex Pistols (1977). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yqrAPOZxgzU&ab_channel=SexPistolsVEVO. This study was conducted within the project Keep it Simple, Make it Fast! Prolegomenons and Punk Scenes, a Road to Portuguese Contemporaneity (1977-2012) (PTDC/CS-SOC/118830/2010) (KISMIF). The project and its results can be found at the site <www.punk.pt>. KISMIF seeks to explore in depth the punk reality in Portugal from a perspective of scene development in the last 40 years. Our intention has been to map and historically typify punk manifestations in Portugal, using extensive and intensive methodologies. The project is funded by FEDER through the COMPETE Operational Program from the Foundation for Science and Technology. It is led by the Institute of Sociology of the University of Porto) and was developed in partnership with the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research and Lleida University.

[2] The title of this article was inspired by the song "Life Ain't Enough For You" by Legendary Tigerman. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9BOuDugqRks&ab_channel=bigfattruckprod

[3] Section title adapted from the lyrics of the song "Hybrid Moments" by Misfits. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wpuHOkPeGJ8&ab_channel=TheMisfits-Topic

[4] There were only 40 people present; however, among them were the members of pioneering and emblematic punk bands, including Howard Trafford and Pete McNeish, who would eventually become known as Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley, the founders of the Buzzcocks, along with artists such as Ian Curtis, Mark Smith, Tony Wilson, and Peter Hook, who would become the bassist for Joy Division, and Morrissey, who would establish himself as the founder of The Smiths.

[5] The group appearing most frequently in our analysis is GASTagus Association. This is a non-profit youth association that develops education projects for citizenship. See https://www.gastagus.org/a-nossa-historia

[6] It is currently the main meeting point for heavy metal fans in the city of Porto, Portugal. More information at: https://www.facebook.com/metalpointclub/

[7] As part of the international network and community connected to the global conference Keep It Simple, Make It Fast! (KISMIF). Available at: www.kismifconference.com