The Values of Live Music Videos on YouTube: A Montreal Case

Montreal nights have long been a particular attraction of the city. They are featured in the public sphere, in debates about crime, insecurity, and transgression on the one hand, and about public cultural life, spectacles, and more recently, gentrification, on the other (Reia 2019, Straw 2015, Barrette 2014). Montreal has been described as a place where nighttime music activities produce specific knowledge and behavior (Straw 2004) and where cultural differences take new shapes, especially those related to class, age, and language (Straw 2019, Della Faille 2005). In this context, live music is crucial in understanding Montreal’s distinctive cultural identity, just as in other cities in the Global North (Picaud 2019). The prominence of Montreal live music relates to a historically weak “hard” music infrastructure (due to the city’s remoteness from the global music industry) that interacts with a dense and meaningful “soft” infrastructure embodied in the concept of the “bohemian enclave” (Stahl 2010).[1]

As a performing art form that often occurs at night, live music is ephemeral and relatively hidden from traditional spaces of public activity. In this sense, live music is challenging to map and assess empirically (Garcia 2013, Mercado Celis 2017). However, platforms such as YouTube, Twitch, and Facebook now work as digital venues and repositories for live music videos produced by both amateurs and professionals. Live music content is part of the abundant catalog that feeds the attention economy on which digital platforms rely. Indeed, audience members now often make and share videos of concerts, creating new forms of live music consumption (Bennett 2015). At the same time, new live performance video formats (including live-streaming) are being produced and broadcast by increasingly professional agents (Holt 2011), despite historical difficulties in monetizing visual content related to popular music (Buxton 2018). These formats rely on a mix of different audio-visual traditions (Holt 2018, Heuguet 2016, Munt 2011, Desrochers 2010) adapted to the “platformized” context of the Internet (Nieborg and Poell 2018, Gillespie 2010). How can we assess and interpret the value of live music videos on these platforms? How do they relate to a sense of place (in this case, Montreal) and other values related to live music?

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Montreal music scenes has been severe, as most shows were canceled. The primary response came in the form of the explosion of virtual concerts. Nevertheless, these shows mainly benefit top mainstream artists and do not compensate for economic and social losses from brick-and-mortar concerts (Spanu 2020). This gap amplifies the necessity to investigate live music in the platformized media context. This article aims to assess the values of live music on digital platforms through the example of live music videos shot in Montreal and broadcasted on YouTube. It relies on the study of an exploratory sample of videos. The results are discussed in terms of heritage value, here understood as the valuation of artifacts associated with a sense of cultural past (Strong 2018, Heinich 2019).

Live Music and the digital heritage of urban cultural scenes

The most common media content related to live music events is flyers, posters, photos, and videos. However, we want to focus on video, as it has become a select format of live performance in the digital media environment (Holt 2011). Therefore, live music videos on digital platforms can be considered, to some extent, an artifact related to a past musical public event embedded in a digital interface. The artifact corresponds to the audiovisual content produced by different participants that depict live music in a particular place (here in Montreal), ranging from professional film concerts to amateur smartphone videos uploaded on a digital platform. In this sense, our definition of live music events and videos is deliberately broad. We separate the analysis of the “valuation process” (Heinich, 2020) of these videos into three phases: 1) agents producing and sharing videos, 2) the audiovisual content of the videos, and 3) the experience made visible by the affordances of the platform's interface.

The values usually associated with live music are economic, social, cultural, and spatial (van der Hoeven and Hitters 2020; Van der Hoeven and Hitters 2019; Holt 2010). This study observes how these values transfer to the digital environment through the case of live music videos from Montreal, using the following definitions: Economic value refers to the commercial dimension of the video producer/broadcaster and the consideration of live music videos as commercial products; public engagement and participation are aspects of social value; spatial value corresponds to a visual sense of place (e.g., the city); and finally, cultural value refers to creativity, diversity, and talent development through the use of videos.

As cultural texts, live music videos relate to broader systems of meaning operating in society (Alper 2014; Ibrahim 2015), mediated by their production conditions, audiovisual qualities, directing choices and contingencies, and pre-existing formats with which they somehow dialogue. Besides, as a broadcasting platform, YouTube entails a series of specificities that require clarification. Contrary to received wisdom regarding their deterritorialization tendencies, digital platforms such as YouTube can reinforce the role of locality in the articulation of music communities (Barna 2017) and shape our understanding of urban spaces (Fazel and Rajendran 2015), which makes them suitable environments to assess how they foster spatial values. Moreover, the very accessible dimension of YouTube understood as social media enhances public participation, which relates to some extent to a form of social value.

Scholars also investigated this platform as a site of heritage practices related to dominant and marginalized cultures, official and non-official sources, and professionals and amateurs (Pietrobruno 2013; Pietrobruno 2018). From an archive studies perspective, YouTube can thus be considered as a sort of database that can transform, under certain conditions, any video content into archival content, especially in comparison with platforms such as Twitch, which is more focused on live streaming and interactivity. However, it is also performative because it is embedded in the present, affecting and mediating contemporary cultural practices and representations (DeCesari and Rigney 2014). This ambivalence represents an essential variable of the following analysis, as it mediates cultural values.

Another critical ambivalence is the functioning of the attention economy on which YouTube relies. Some features such as the comment section and the view number refer simultaneously to social and economic values. For instance, the view count represents a driving feature for the user experience and perception of relevance on the one hand (Feroz Khan and Vong 2014) and a contradictory technical system of valuation that relates to monetary values on the other hand (Heuguet 2020). Further, the functioning of the platform is highly dependent on its curation system. In a certain way, YouTube belongs to the same genealogy as other archive apparatus that store a vast majority of content and only display a minority through the action of a curatorial authority (Prelinger 2009). However, this topic exceeds the purpose of this paper; we will only address it marginally.

Finally, YouTube uses a tool (Content ID) to automatically identify copyrighted content, and better manage official content and remunerate owners (which corresponds to a historical challenge within cultural industries and a vision of content as a product). However, this technology needs to conceptualize music as fixed data (Heuguet 2019). This raises questions, as live music content necessarily differs from the “original” recorded version. Moreover, copyright management is particularly complicated in live video recordings, as the rights are fragmented between the artist, the label, the audiovisual producer, and the show promoter. This complexity profoundly influences the circulation of live music videos on digital platforms, especially in the case of professional video production (Guibert, Spanu and Rudent 2021).

Methods and corpus

Based on previous argumentation and visual methods applied to social media (Hand 2016), my exploration of live music videos’ values on YouTube considers three aspects:

1) The conditions and participants involved in the production and broadcasting of live music videos on YouTube (name of the channel, number of followers, other videos hosted by the channel, profile description)

2) the visual content (video title, date, sound, visual elements, composition, and effects)

3) the specific mediations embedded in the platform that affect the experience (comments, number of views, recommendation).

A first exploratory sample of data was collected using the keyword “live music Montreal” and its French equivalent in the YouTube search bar. The results were filtered alternatively by view counts and relevance. A second sample was collected based on two iconic independent venues in Montreal: La Sala Rossa and Casa del Popolo (both owned by the same local company, founded in 2000 by Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s band member Mauro Pezzente). The final qualitative sample corresponds to a total of 22 videos. The data collection was not restricted to a specific timeframe. Eventually, the live events broadcasted in the sample ranged from 1979 to 2019. The complete list of videos from the sample and their description can be accessed here: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Data_What_the_night_used_to_be_-_Montreal/12410591

Results and discussion

Agents: Music industry, digital DIY archivists, local and global, and promoters/broadcasters

The range of agents involved in producing and broadcasting YouTube videos taken from live music events in Montreal is extensive. On the one hand, the most popular live music content usually refers to one official artist’s channel, such as Belgian artist Stromae or American artist Rihanna. The VEVO logo featured in the videos validates the content as a product of the mainstream music industry. Here the channels’ value is partly commercial, as the objectives are to expand the artist’s notoriety and give fans new material through which to engage with the artist. Therefore, these channels fall to some extent into the commercial category thanks to the economic conversion of their social measurement (number of followers, numbers of views) by which YouTube operates. In a way, these channels work as a digital back catalog that complements other official content related to the artist on other media. The financial value of these concert movies is relatively low, compared to the gross value of a global tour, for instance (mainly because of YouTube’s revenue sharing policy); however, they can be a source of other forms of value. Indeed, this type of official artist’s channel usually features many different videos, from interviews to intimate shows and music videos, and ultimately works as artists’ personal archives. In this sense, it has a particular cultural value, albeit moderated by the fact that it only concerns one artist.

On the other hand, non-official channels can also feature equally praised live music content, which complicates the classification and value of the agents involved. The most viewed video in the sample, Queen’s classic 1981 concert at the Forum de Montreal, particularly illustrates this phenomenon. The video was filmed by a professional crew as official content, but it was anonymously posted by a non-official channel (the volunteer-powered French news website AgoraVox).

The user does not own the movie’s rights, which means that the video remains on the platform because the right-holders decided not to block it and/or ContentID did not identify it. Interestingly, and despite the band’s immense notoriety, this video benefits from two complementary factors: professional audiovisual quality on the one hand and no copyright restriction on the other. It represents a gray area that benefits the circulation of content related to live music in Montreal and where music industry interests are left aside. In this sense, the channel’s value is cultural above all, as it brings an archive from an important past event to a larger audience. However, such value remains fragile as the platform or the channel can delete the content at any time.

More generally, most channels in the sample are from broadcasters that are not directly involved in the organization of music events or performances. A significant part of the sample of YouTube channels are run by amateurs specialized in broadcasting mainly local live music. As they are amateurs, their activity confers substantial affective cultural value (Long et al. 2017), related either to an artist or a genre of music. See, for instance, the case of Montreal Hclive (a channel of hardcore shows in Montreal, see Figure 3), tangotrash (which broadcasts indie live music events that occurred between 1997 and 2003 in different venues of Montreal, see Figure 4), MelAuz (which broadcasts mainstream pop shows and the “Mondial des cultures” festival) or nameless6794 (a fan page dedicated to Montreal’s singer songwriter Grimes). These agents represent DIY archivists of Montreal live music. As their video production and broadcasting activities mainly relate to shows in Montreal, they also value a sense of place, sometimes through a mention in the channel name (e.g., Montreal Hclive).

In other cases, YouTube channels are administered by professional entities, companies, or media that develop more activities beyond broadcasting live music videos. These activities can complement each other, in the way that live music video production often works as a platform for other activities. For instance, the channel SBKZ Media covers salsa events and provides digital marketing services; the channel Mediavision Cinematic Wedding Films + Photography specializes in both music events and weddings (mainly among the Indian and Pakistani diaspora, see Figure 5). Another relevant example is Montreality, a digital media publication specializing in hip hop featuring live video music and interviews with North American rappers (see Figure 6). The value of these channels oscillates between promotional, cultural, and sometimes spatial; thus, they can be categorized as local live music video broadcasters. Their video content is usually more homogenous, well-indexed, and described in comparison with DIY archivists. However, they share the emphasis on the local, sometimes explicitly in their channel name (e.g., Montreality, Montreal Hclive). As such, they simultaneously bring to light the physical-virtual component of many music scenes and perform the role of the city of Montreal in the articulation of these specific scenes (hardcore punk and metal, hip hop, etc.).

The last group under consideration is the agents who participate in music events in Montreal and broadcast them, of which we mention three examples. First, Slut Island is a DIY festival focused on the queer community that broadcasts short videos of the festival (see Figure 6). Their videos have no promotional or aesthetic purpose; they work as a self-engineered archive of the local queer community. The two other examples are the London-based companies Boiler Room and Sofar Sounds (Figures 7 and 8), both specialized in broadcasting music events in different music genres (electronic and indie pop, respectively). They function as both global event promoters and video broadcasters, and their measured social impact far surpasses any of the other broadcaster channels, accounting for, respectively, two million four hundred thousand and one million followers at the time of the study. Interestingly, they rely on a feedback effect between video and the physical event that results in a “digital media event” perspective, meaning that the musical event is specifically designed to be broadcasted. In this sense, their videos differ from most of the other channels, but their broadcasting activity can complement other activities in a similar vein as other channels. This is especially the case for Sofar Sounds, whose business model relies on selling tickets for “secret” shows that they record and use as “advertising” on YouTube. However, YouTube’s interface turns these channels into more than advertising tools, as they feature a significant number of videos in the shape of an archive or playlist. As such, their value as channels is as much promotional as cultural. Besides, as global broadcasters, these channels participate in building a certain global symbolic status around Montreal’s musical events, as they establish links with other cities in the world where the scene is “happening,” as we shall see in the next section.

Visual content, between document and video performance

In order to assess the different kinds of value of live music video content on YouTube, we have to understand how these formats work. Most videos rely on a traditional format of “concert film,” in which the visual attention is on the artist on stage, while the portrayal of the audience remains marginal and anonymous (see Figures 10, 11 and 12). Interestingly, both professional and amateur videos use that format, although professional videos have better production conditions (multicam, edited sounds and images, etc.). They are commercial/promotional products from the music industry to some extent. However, the value of these videos is also cultural. They portray an artist’s performance and the entire “stage narrative,” reinforcing the opposition between darkness and light, stage and audience. In other words, it reinforces the “exclusive” dimension of the concert and the separation between the artist and the audience, which relies on a particular conception of cultural authenticity (Frith 2007). In the case of amateur videos, it also reinforces a specific type of fan attitude where the attention is on the artist, such as in the case of Grimes’ video posted by a fan (see Figure). More generally, despite their differences regarding production techniques, budgets, and direction choices, both professional and amateur videos relying on this format try to preserve the original spirit and narrative of the performance (sometimes the full length of the show, sometimes just one or a couple of songs). These videos thus represent “traces,” “testimonies,” or “documents” of the actual concert with a specific focus on the cultural performance on stage.

The spatial value of these videos relies on a mention of the venue or the city in the video title or description, creating a semantic link with the location, but the visual content in itself does not show any spatial element (from the venue or the city, for instance). In the case of professional concerts portraying massive crowds, the sense of place is only semantic and not visual, contrasting with other popular Canadian visual media that strongly rely on local geography (Laforest 2019). The video content could almost be filmed anywhere. But the semantic valuation of the city is relevant because the placelessness of the video content is being compensated for, creating a narrative around the video and the concert. For instance, in the case of Belgian artist Stromae, who sings in French, filming the performance in Montreal reinforces the sense of a cultural connection through the francophone world; it seems a conscious choice. In the case of foreign mainstream artists such as Queen or Rihanna, the mention of Montreal in the title foregrounds the importance of the city and its venues for the music industry; Montreal represents a mainstream cultural metropolis in the North American region.

Outside the usual format of the concert film, our sample contains a great heterogeneity of formats and values. For instance, some videos only focus on audience participation. This is especially the case for events that were designed to trigger an active and creative response from the audience, for instance through dancing (Figure 15). In this case, the audience becomes the show, and the main value is the social participation of the public.

Extended audience participation is also present in many DIY videos. Most of them consist of a single shot of the performance from the audience’s perspective with direct messy sound, which emphasizes the audience’s presence but undermines the artist’s performance from a traditional aesthetic perspective. The audience’s presence is not always attractive, as it generally accompanies technical deficiencies, but in some cases, it represents an important visual aspect consciously integrated into the video. See, for instance, hardcore and metal videos (Figures 16 and 17), where participants actively engage in the “mosh pit.” Other aspects of audience participation, such as singing along and soft dancing, can be heard and/or seen in other videos (Figure 18). This lo-fi aesthetic accounts for a more desacralized conception of live music and a closer physical and intimate relationship with the performing artist (Rudy and Citton 2014).

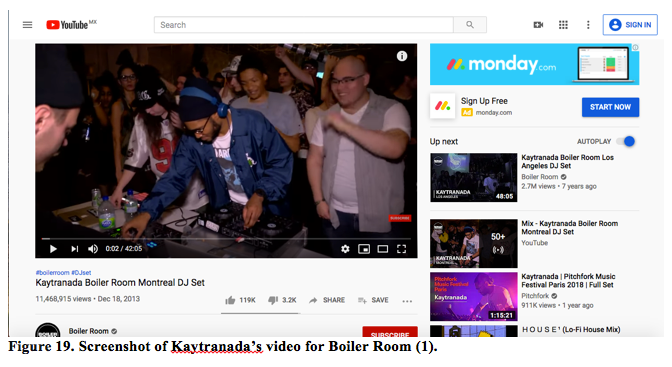

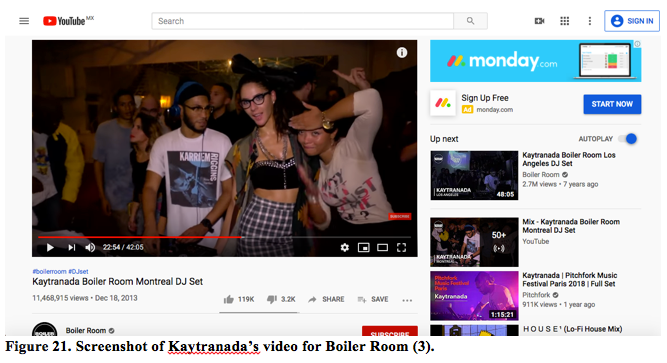

Montreal DJ Kaytranada’s video for Boiler Room is unique in highlighting both the artist’s performance (cultural value) and the audience’s participation (social value). The audience “performs” in front of the camera (alongside and behind the artist), producing an effect of both realism and idealization typical from Boiler Room videos (Heuguet 2016). The faces and bodies of both the artist and the audience are at the center of the video, while Kaytranada’s DJ set remains the sound focal point. In this specific case, the audience draws most of the visual attention (Figures 19, 20, 21), as the interactions between participants follow a drama-like pattern or, as someone in the comment section puts it, a documentary on human behavior in a musical context.

Most other videos from the promoter/broadcaster group also depict the audience quite extensively, emphasizing their social value, but mainly in an idealized way, through dynamic video edition that alternates short takes of the audience and longer ones for the artist’s performance. For instance, the audience seems enthusiastic and chic in Imran Khan’s urban pop concert in a nightclub (Figure 22), but it is quieter and focused at Pomme’s intimate acoustic performance in a café for Sofar Sounds (Figure 23). In these two cases, the YouTube channels work as a platform for other business activities. The videos follow the path of the “aftermovie” format that festival promoters use to increase entanglement between the live music industry and the digital attention economy (Holt 2018). In a way, these videos perform liveness more than they document or portray it.

This specific type of video performance also fosters a more diverse sense of place, as it tends to include more visual elements related to music venues. For instance, DIY videos in small venues are generally shot from the front rows, emphasizing the proximity between the artist and the audience. They also show specific features of the venue: walls, curtains, and tables, which highlight the role and specificity of physical places in the music experience, whereas videos in large venues mainly focus on the performance and/or the immensity of the audience. For instance, small venues such as Casa del Popolo and Sala Rossa constitute, on the one hand, a platform for niche music (hardcore, metal), and on the other hand, an essential step for a future international and successful career, either for foreign artists (Charli XCX) or local ones (Grimes). This aspect is not specific to Montreal, but it contributes to the narrative of the music city through small venues’ cultural, social, and spatial value.

Finally, this analysis highlights a specific ideological framework that we will call cosmopolitan, given the diversity of racial and gender representations, from white male and female identities (Charli XCX, Romes, The Lemon Twigs) to the queer community (Pelada) and local diasporas (Imran Khan and Mohammed Rafi).[2] In terms of language, both French and English are represented. As a result, these videos reflect both a global trend within popular music and a dominant narrative about Canada’s and Montreal’s apparent openness and multiculturalism. They contrast partially with white francophone identities that dominate Québec’s audiovisual media, especially cinema (Loiselle 2019).

Platformized reception and use value

As a digital interface, YouTube is known for attributing value to the videos through number of views. In many cases, such measurement corresponds to the cultural recognition of an artist that can translate into economic value. However, this number has to be high enough to be substantial, as in the case of Stromae, Rihanna, or Boiler Room videos, which have more than several million views. In these cases, the financial benefit fits the model of YouTube channels that are integrated into the music or media industry. However, channels with no economic purpose or rights to manage, such as those of AgoraVox or the amateur musician who posted Mohammed Rafi’s video, reaching a high number of views (over 2 million) mainly corresponds to cultural, rather than financial, interest.

This view measurement also works as a curation tool. Highly viewed videos are more visible on the platform, but the search engine also has a “most popular” option for hierarchizing content, which explains Mohammed Rafi’s presence in the sample, for instance. More generally, the view count is not only a neutral indicator of cultural and economic value; it also carries a particular value as a measurement tool integrated into the interface where content is experienced. In other words, its presence on the screen affects the experience of the video. For instance, a higher number of views enhances the feeling of sharing an experience with a broader audience. Similarly, a small number of views does not necessarily mean low relevance, but nicheness, in the sense of content only known by a happy few, as in the case of Grimes’ video at the beginning of her career. Here, then, the relatively low view count also reflects a social value, specifically within the Montreal local music scene.

The comment sections of the channels also carry value that can be assessed. Here, two elements are particularly relevant: the number of comments (usually proportional to the view count), and the comments’ content. This comment section offers viewers a more active form of participation than a simple view; here, commenters tend to express express admiration of the artist or nostalgia about the performance in the video. In other words, audiences from the comment section value these videos as cultural content related to an artist’s general “persona” (Auslander 2021) and, especially, the physical encounter during a concert. Other marginal comments include jokes, criticism of the artist or the video, calls for other users who share the same taste (e.g., “who keeps listening to this in 2021?”), reflecting the values of social interaction and shared interests.

The comment section can seem trivial at first, but it participates in constructing the video’s meaning and triggers desires and fantasies regarding democratic participation (Carpentier 2014). The most iconic case is Kaytranada’s video for Boiler Room, which has over eleven million views and over twelve thousand comments, a higher ratio than any other video in the sample. (Queen’s video, by contrast, has twice the views and just under ten thousand comments). The example below demonstrates how comments can be considered not only as separate content but as providing new interpretations of a video:

1:20 guy on the right gets rejected, 4:06 he thinks the girl came for him yet the girl came for Kay, 4:29 gets another chance with some other girl, 4:58 he tries to use Kaytranada’s mic with no success, 5:28 gets rejected again, 5:54 gets bullied, 6:08 probably asks for something and gets ignored.. poor guy (YouTube comment).

This comment offers an alternative version of the video, with a specific chronology mixed with judgment and humor regarding the crowd’s participation. As mentioned in the previous section, Boiler Room videos already emphasize the audience’s presence, but this comment stresses audience interaction even more, transforming it into a sort of short drama. The fact that users can comment and indicate that they “like” other comments adds another layer of intertextuality to the video. Some comments are “liked” by thousands of users, making them appear on the top of the comment section. In some rare but relevant cases, comments take the shape of debates and controversies regarding the scene’s values:

Let’s clear a few things: -Haters need to stfu [shut the fuck up]. Everyone was just having fun. We in Montreal are incredibly proud of Kaytra and it was damn great to just have fun and dance to the homie’s killer set. Most Boiler Rooms only has people on their cellphones. Montreal is that city. -Fat Joe look-alike is one of Kaytra’s closest friends, they went to HS together, him not being the best dancer ever doesn’t mean shit, he belonged as much as anyone. -Guy who combs his fro around the 2 minutes mark is High-Klassified and he also had a set during that BR, a sick producer who’s part of Alaiz, the same collective Kaytra is part of. [...] -Light-skin girl who dances her ass off is a good friend of Kaytra, and she’s not doing it for the camera, she dances like hell whether the cams are there or not. She also sings: https://soundcloud.com/stwosc/virgo [...] -There were definitely a few people on molly that night, but not more than half. The other half is just people who support the local talent and enjoy the hell out of the music (YouTube comment).

Here the values debated and articulated are the following: cultural value (the centrality of the music and dance vs. using drugs or “hitting on” other people), social (diversity of people and bodies), and spatial (the uniqueness and openness as characteristics from Montreal). YouTube comments, then, constitute a social form of participation; moreover, they showcase different values concerning the video content. In some instances, the comment section becomes a public sphere that extends other media and physical spaces of cultural, social, and spatial valuation.

Conclusion

After being bought by Google, YouTube moved from a user-generated content platform to a more professional and commercial one that increasingly incorporates traditional media patterns (Kim 2012). In fact, this study has shown that a significant part of live music videos adapts positively to the attention economy and platform capitalism, especially official content that can generate revenue or fuel other commercial activities. However, YouTube remains a versatile tool for the music scene’s media exposure, social interaction, and cultural memory. In the case of the Montreal music scene, there is an immensity and diversity of material available, between promotional, expressive, and archival content. YouTube channels also represent ambivalent intermediaries, between local and global broadcasters interested in unique content, DIY archivists’ passionate work, and the music industry’s commercial goals.

These varying interests should contribute to an alternative understanding of cultural heritage shaped by the specific values fostered by digital platforms such as YouTube (Bennett and Rogers 2016; Malpas 2008). Based on the present work and previous research on the same topic (Pietrobruno 2013; Pietrobruno 2018), such understanding should consider 1) unofficial, commercial, and non-institutional participants, 2) a diversity of formats, including amateur and professional, document and performance paradigms, and 3) social participation with affordances such as view metrics and comments mediating the content experience. Indeed, as live music videos on YouTube foster a sense of musical past through a complex set of values, they digitally extend ordinary, ephemeral, and heterogeneous practices that were theorized as heritage as praxis (Strong and Whiting 2018). They refer to the increasing integration of music in daily life activities through technology (Hagen 2016), especially popular music events from the past that have received very little attention from professional heritage institutions.

The practices and values described here relate to some extent to flexible, participatory, and decentralized practices within intangible heritage projects (Pianezza 2020). Although the academic interest in popular music heritage has dramatically increased over the last decade (Roberts and Cohen 2014; Cohen et al. 2015), contributing to the recognition of a diversity of heritage participants, practices, and objects (Brunow 2019; van der Hoeven 2015), digital platforms remain insufficiently addressed (Nowak 2019). A consideration of the value of YouTube live music videos can enrich our conception of heritage in a context of increasing financial and symbolic investment from public and private entities into cities’ music heritage (Baker et al. 2020; Baker et al. 2018; Ross 2017). Indeed, these YouTube videos showcase a great diversity of artists who have participated in Montreal’s cultural past. Nevertheless, the fact that some of the content has already disappeared or might disappear at some point makes the discussion of YouTube as a heritage tool all the more urgent (Cambone 2019).

References

Auslander, Philip. 2021. In Concert: Performing Musical Persona. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Baker, Sarah, Raphaël Nowak, Paul Long, Jez Collins, and Zelmarie Cantillon. 2020. “Community Well-Being, Post-Industrial Music Cities and the Turn to Popular Music Heritage.” In Music Cities. New Directions in Cultural Policy Research, edited by Christina Ballico and Allan Watson. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baker, Sarah, Lauren Istvandity, and Raphaël Nowak. 2018. “Curatorial Practice in Popular Music Museums: An Emerging Typology of Structuring Concepts.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23(3):434–453.

Barna, Emilia. 2017. “The Perfect Guide in a Crowded Musical Landscape: Online Music Platforms and Curatorship.” First Monday 22(4).

Barrette, Yannick. 2014. “Le Quartier des spectacles à Montréal : la consolidation du spectaculaire.” Téoros 33(2).

Bennett, Andy, and Rogers Ian. 2016. Popular Music Scenes and Cultural Memory. Pop Music, Culture and Identity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bennett, Rebecca J. 2015. “Live Concerts and Fan Identity in the Age of the Internet.” In The Digital Evolution of Live Music, edited by Angela Cresswell Jones and Rebecca Bennett, 3–15. Amsterdam: Chandos.

Brunow, Dagmar. 2019. “Manchester’s Post-punk Heritage: Mobilising and Contesting Transcultural Memory in the Context of Urban Regeneration.” Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research 11(1):9–29.

Buxton, David. 2018. “La vidéo musicale comme ‘marchandise échouée’.” Volume! 14(1):193–200.

Cambone, Marie. 2019. “La médiation patrimoniale à l’épreuve du ‘numérique’: médiation patrimoniale, médiation documentaire et médiation expérientielle.” Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication 16.

Carpentier, Nico. 2014. “‘Fuck the Clowns from Grease!!’Fantasies of Participation and Agency in the YouTube Comments on a Cypriot Problem Documentary.” Information, Communication & Society 17(8):1001–1016.

Cohen, Sara, Robert Knifton, Marion Leonard, and Les Roberts. 2015. Sites of Popular Music Heritage. London: Routledge.

DeCesari, Charia, and Ann Rigney. 2014. Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.

Della Faille, Dimitri. 2005. “Espaces de solidarités, de divergences et de conflits dans la musique montréalaise émergente.” Volume! 4(2):61–73.

Desrochers, Jean-Philippe. 2010. “Les vidéastes de la Blogothèque: travailler à la réinvention de la captation des prestations musicales.” Séquences: la revue de cinéma 268:12–13.

Fazel, Maryam, and Lakshmi Rajendran. 2015. “Image of Place as a Byproduct of Medium: Understanding Media and Place through Case Study of Foursquare.” City, Culture and Society 6(1):19–33.

Feroz Khan, Gohar, and Sokha Vong. 2014. “Virality over YouTube: An Empirical Analysis.” Internet Research 24(5):629–647.

Frith, Simon. 2007. “Live Music Matters.” Scottish Music Review 1(1):1–17.

Garcia, Luis Manuel. 2013. “Doing Nightlife and EDMC Fieldwork.” Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5(1):3–17.

Gillespie, Tarleton. 2010. “The Politics of ‘Platforms’.” New Media & Society 12:347–364.

Guibert, Gérôme, Michaël Spanu, and Catherine Rudent. 2022. “Live shows and more. Filming musical performance: the development of an economic sector in France.” In Researching Live Music: Gigs, Tours, Concerts and Festivals, edited by Chris Anderton and Sergio Pisfil. London: Routledge.

Hagen, Anja Nylund. 2016. “Music Streaming the Everyday Life.” In Networked Music Cultures. Pop Music, Culture and Identity, edited by Raphaël Nowak and Andrew Whelan, 227–245. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Hand, Martin. 2016. “Visuality in social media: researching images, circulations and practices.” In The SAGE Handbook of social media research methods, edited by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase, 215–231. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Heinich, Nathalie. 2019. “Axiologie du précieux. Essai de modélisation.” Gradhiva 30(2):92–107.

------. 2020. “A Pragmatic Redefinition of Value(s): Toward a General Model of Valuation.” Theory, Culture & Society 37(5): 75–94.

Heuguet, Guillaume. 2020. “Vues vérifiées, écoute évacuée : la valorisation publicitaire de la musique sur YouTube.” Tic & Société 14(1-2):95–129.

------. 2019. “Vers une micropolitique des formats. Content ID et l’administration du sonore.” Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances 13(3):817–848.

------. 2016. “When Club Culture Goes Online: The Case of Boiler Room.” Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 8(1):73–87.

Holt, Fabian. 2018. “Music Festival Video: A ‘Media Events’ Perspective on Music in Mediated Life.” Volume! 14(1):211–225.

------. 2011. “Is Music Becoming More Visual? Online Video Content in the Music Industry.” Visual Studies 26(1):50–61.

------. 2010. “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13(2):243–261.

Holt, Fabian, and Wergin Carsten. 2013. Musical Performance and the Changing City: Post-Industrial Contexts in Europe and the United States. London: Routledge.

Kim, Jin. 2012. “The Institutionalization of YouTube: From User-Generated Content to Professionally Generated Content.” Media, Culture & Society 34(1):53–67.

Laforest, Daniel. 2019. “The Emotional Geographies of Québécois Cinema.” In The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Cinema, edited by Janine Marchessault and Will Straw, 212–228. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Loiselle, André. 2019. “Popular Quebec Cinema and the Appeal of Folk Homogeneity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Cinema, edited by Janine Marchessault and Will Straw, 367–389. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Long, Paul, Sarah Baker, Zelmarie Cantillon, Jez Collins, and Raphaël Nowak. 2019. “Popular Music, Community Archives and Public History Online: Cultural Justice and the DIY Approach to Heritage.” In Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity, edited by Jeannette A. Bastian and Andrew Flinn, 97–112. Cambridge: Facet.

Long, Paul, Sarah Baker, Lauren Istvandity, and Jez Collins. 2017. “A Labour of Love: The Affective Archives of Popular Music Culture.” Archives and Records 38(1):61–79.

Lussier, Martin. 2015. “Le quartier comme production culturelle: du développement économique municipal au développement culturel des quartiers à Montréal.” Canadian Journal of Communication 40(2).

Malpas, Jeff. 2008. “New Media, Cultural Heritage and the Sense of Place: Mapping the Conceptual Ground.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 14(3):197–209.

Mercado-Celis, Alejandro. 2017. “Districts and networks in the digital generation music scene in Mexico City.” Area Development and Policy 2(1):55–70.

Munt, Alex. 2011. “New directions in music video: Vincent Moon and the ‘ascetic aesthetic’.” Text 11.

Nieborg, David B., and Thomas Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20:4275–4292.

Nowak, Raphaël. 2019. “Questioning the Future of Popular Music Heritage in the Age of Platform Capitalism.” In Remembering Popular Music's Past: Memory-Heritage-History, edited by Lauren Istvandity, Sarah Baker, & Zelmarie Cantillon, 145–158. New York: Anthem Press.

Nowak, Raphaël and Sarah Baker. 2018. “Popular Music Halls of Fame as Institutions of Cultural Heritage.” In The Routledge Companion to Popular Music History and Heritage, edited by Sarah Baker, Catherine Strong, Lauren Istvandity, Zelmarie Cantillon. London: Routledge.

Pianezza, Nolwenn. 2020. “Les écritures médiatiques partagées de la mémoire – patrimonialisation et paradigme de l’immatériel.” Communication & langages 203(1):175–195.

Picaud, Myrtille. 2019. “Putting Paris and Berlin on Show: Nightlife in the Struggles to Define Cities’ International Position.” In Nocturnes: Popular Music and the Night, edited by Giacomo Botta and Geoff Stahl, 35–48. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. 2013. “YouTube and the Social Archiving of Intangible Heritage.” New Media & Society 15(8):1259–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812469598

Pietrobruno, Sheenagh. 2018. “YouTube Flow and the Transmission of Heritage: The Interplay of Users, Content, and Algorithms.” Convergence 24(6):523–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516680339

Prelinger, Rick. 2009. “The Appearance of Archives.” In The YouTube Reader, edited by Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau, 268–274. New York: Columbia University Press.

Reia, Jess. 2019. “Can We Play Here? The Regulation of Street Music, Noise and Public Spaces After Dark.” In Nocturnes: Popular Music and the Night, edited by Giacomo Botta and Geoff Stahl, 35–48. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Roberts, Les, and Sarah Cohen. 2014. “Unauthorising Popular Music Heritage: Outline of a Critical Framework.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20(3):241–261.

Ross, Sara G. 2017. “Development versus Preservation Interests in the Making of a Music City: A Case Study of Select Iconic Toronto Music Venues and the Treatment of Their Intangible Cultural Heritage Value.” International Journal of Cultural Property 24(1):31–56.

Rudy, Dario and Yves Citton. 2014. “Le lo-fi: épaissir la médiation pour intensifier la relation.” Écologie & politique 48(1):109–124.

Spanu, Michaël. 2020. “Lo que queda de la música en vivo en tiempos de cuarentena.” UNAM Global.

Stahl, Geoff. 2010. “Music Making and the City: Making Sense of the Montreal Scene.” In Sound and the City, edited by Dietrich Helms, 141–159. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag.

Straw, Will. 2019. “Imaginaires et politiques de la nuit montréalaise.” L'Observatoire 53(1):29–32.

------. 2014. “Scènes: ouvertes et restreintes.” Cahiers de recherche sociologique 57(3):17–32.

------. 2004. “Cultural Scenes.” Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure 27(2):411–422.

Strong, Catherine. 2018. “Burning Punk and Bulldozing Clubs: The Role of Destruction and Loss in Popular Music Heritage.” In The Routledge Companion to Popular Music History and Heritage, edited by Sarah Baker, Catherine Strong, Lauren Istvandity, and Zelmarie Cantillon, 180–188. London: Routledge.

Strong, Catherine, and Samuel Whiting. 2018. “‘We Love the Bands and We Want to Keep Them on the Walls’: Gig Posters as Heritage-as-Praxis in Music Venues.” Continuum 32(2):151–161.

Sutherland, Richard. 2015. “Inside out: The Internationalization of the Canadian Independent Recording Sector.” Canadian Journal of Communication 40(2).

Van der Hoeven, Arno, and Erik Hitters. 2019. “The Social and Cultural Values of Live Music: Sustaining Urban Live Music Ecologies.” Cities 90:263–271.

Van der Hoeven, Arno, and Erik Hitters. 2020. “The Spatial Value of Live Music: Performing, (re)Developing and Narrating Urban Spaces.” Geoforum 117:154–164.

Van der Hoeven, Arno. 2015. “Narratives of Popular Music Heritage and Cultural Identity: The Affordances and Constraints of Popular Music Memories.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 21(2):207–222.

Notes

[1] With the international success of indie acts like Arcade Fire and Grimes in the 2000s and 2010s, the local scene reinforced its ties with the global music industry and found support from local public authorities seeking to take advantage of this new cultural aura (Sutherland 2015, Lussier 2015).

[2] Pelada is a Montreal-based electro-punk duo singing in Spanish. The queer reference comes from expert commentators. See, for instance, their presentation on the Resident Advisor platform mentioning the exploration of “gender politics.” Link: https://ra.co/dj/pelada-ca/biography. Imran Khan is a Dutch-Pakistani “urban pop” singer particularly famous within the Indian-Pakistani diaspora worldwide. Mohammed Rafi was an Indian singer internationally known for his songs in many languages and lip-syncing in movies.