Live Performance and Filmed Concerts: Remarks on Music Production and Livestreaming before, during, and after the Public Health Crisis

I am going to make a few analytical observations on live music in France and especially concerning the distinction between “in-person” and “remote” events, which took on a new meaning during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the first section, I will explore the rise of digital media as a worldwide phenomenon, its impact on the concert production and broadcasting sector, and in particular, the emergence of livestreams as an opportunity for value creation. As I will show in the second section, however, the development of music livestreaming on platforms was initially only of relatively low importance. In terms of how the production sector functions, I consider the conventions in use and the music industry’s legal framework of the concert economy and concert broadcasting in France as my field of inquiry. The lockdown periods in 2020 and 2021, brought previously hidden mechanisms to the forefront which can now be assessed.[1] Lived experience has thus forced the various live music stakeholders to set out their positions with respect to the filming of concerts and their broadcasting through audio-visual media and digital platforms (livestreams). They have positioned themselves individually or collectively through unions or federations.

Is a concert viewed on-screen partly a concert, or is it simply an audio-visual program offered to the viewer? Lockdown brought about reorientations in organizational structures, particularly the relations maintained by the companies’ directors with the different stakeholders in the concert environment (Fligstein 1996). As I will show here, opinions on the value of livestreams coalesce strongly through isomorphism among companies involved in the same activities within the organizational field of production (Di Maggio and Powell 1983). Divergences in perspectives can be very pronounced between companies, depending on where they sit in the chain of production.

The extent and duration of the shock brought about by the pandemic and the public health crisis have led to a notable change in strategy among various stakeholders since the end of 2020, away from performance sector representatives or the concert filming industry. This change was at first driven by intermediary technical service providers (such as cameramen whose work falls somewhere between production and broadcast) but was also supported by live concert venues. I will explore the various elements in this process in the last section of this chapter.

The growth in the broadcasting of live performance and concerts by audio-visual media and online platforms during the public health crisis

When we look at the musical offering on the supply side and study the way the production sector functions both upstream and downstream, from artists to audiences, we generally talk about two types of consumer offerings: on one hand, the concert (a “performing arts” event or a “live performance”) and on the other, recorded music, marketed by the cultural industries (Frith 2007; Laing 2021).[2] For concerts, preoccupations surround the success of an event with a limited audience at a given time, existing within the framework of predefined maximum capacities and with revenue through the sale of tickets at given prices. Recorded music, however, aims to attract audiences through a whole range of formats sold in the form of published products or as flows (Miège 2000). Although the success of recorded music can be uncertain (Adler 1985; Guibert et al. 2016), revenue is not limited by time and space. As a result, concerts, which are high risk, not very lucrative, and do not provide any excess returns for promoters (Baumol and Bowen 1966) were for a long time a neglected part of the music economy (Hirsch 2001). As they didn’t generate any potential for profit, they were – at least when it came to festivals – managed by the not-for-profit sector for many years up until the recorded music crisis in the early twenty-first century.

Filmed concerts occupy a hybrid position in terms of their existence as a product and a process. Marketed for a long time on physical formats (live albums, VHS cassettes, DVDs, etc.) or broadcast on mass media (television, VOD platforms), they used a similar economic model to that of documentary films, experimental films, or other audio-visual works.[3] They were, then, in the second half of the twentieth century, akin to other goods and services marketed by cultural industries (Bouquillion 1992; Holt 2020).

Muddying the waters — Livestreaming: a particular situation

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, however, both our professional and leisure lives have been significantly affected by the democratization of the Internet in everyday life (Martin and Dagiral 2016). The conditions of production and reception of music have been displaced (Bennett 2012), calling the definition of live performance into question (Heuguet 2021). The term “livestreaming” is used to describe the broadcasting of music played live, or at least under live performance conditions, or rather at least reproducing live performance conditions (Bourdon 1997).[4] Live forums or other premium service offerings (virtual backstage access, special artist comments, concert merchandising, goodies, etc.) are very much part of such broadcasts. The processes associated with livestreaming gradually came into being just as live performance and its media representation took on additional importance in the context of the crisis of recorded music sales over the last twenty years. With larger maximum audience sizes and the distancing of crowds from the stage during performances (Guibert and Eynaud 2014), screens were introduced for those audience members who were furthest from the stage (Leveratto et al. 2014). Moreover, the practice of broadcasting for audiences who were present virtually but not physically developed with or without the agreement of artists and rights holders, particularly through social media.

As the pandemic extended across the world during the first quarter of 2020, this type of televised musical performance was promoted — first in the form of audio-visual “post cards” filmed simply and posted spontaneously — with artists facing the camera from their lofts, bathrooms, kitchens, living rooms, cellars, or gardens and accompanying themselves with pianos, guitars, or other acoustic musical instruments. These performances were seen as promotional tools for artists rather than concerts for which a ticket price was paid. This was prior to the advent of big productions with deliberately designed protocols requiring significant investment and the purchase of tickets by spectators using the “traditional” concert and festival model. Economically speaking, the issue then coalesced around two aspects (Midem 2021:14), the first of which — revenues — concerns formulas in regard to the promotion of artists (to sell recordings and obtain concert bookings) through monetization (“pay-per-view” through video on demand), and the second — costs — related to performances ranging from do it yourself shows set up by fans or artists, to productions organized by live performance or audio-visual production professionals.

Is a new balance regarding the economy of audio-visual filming for broadcast (from production to consumption) beginning to see the light of day? Having worked on the issue of concert filming since 2010 (Guibert 2020), I have had the opportunity of gathering together the perspectives of the various professional groups involved in live music. We know that the social sciences are generally characterized by the impossibility of carrying out experiments at a macro-sociological level to test the importance of explanatory variables (Passeron 1991) — such experiments are indeed thought to have an irreversible impact on the social sphere. Throughout the world, however, in the course of the first half of 2020, the pandemic caused an external shock of such magnitude that a number of practices and customs were called into question. Collective gatherings (including live concerts) were controlled or forbidden as a result of public health measures. In France, maximum audience sizes were reduced to five thousand people at the beginning of 2020, then to a thousand and one hundred, and public places were closed entirely at the end of March of the same year. Some businesses saw their revenues fall to zero (the sale of tickets for concerts, for example), while others drastically increased (online sale of goods on Amazon.fr). Divisions thus appeared at the heart of sectors that were previously related. While musicians were prohibited from giving concerts, cameramen have never had such freedom in terms of the conventions and techniques associated with their profession. They have been given such license to film performing musicians because the only possible onstage performances are those that take place in venues without an audience and with social distancing between the people working there.[5]

Live shows versus livestreams: Two distinct industry postures

I will show here that concert filming and livestreams can’t be seen as logical progressions of each other, because they are tools used by two virtually independent production sectors.

Live music promoters and related rights (droits voisins)

Concerts require a complex technical infrastructure in a specific place: where the event takes place, whether this is a concert venue or a festival. Under French law — and in contrast to many other countries — the promoter is the employer booking artists (Guibert and Sagot-Duvauroux 2013). Work is required for the set design, sound, light and artistic performance. So why not film the concert and make a show that could be sold? It could, for example, be broadcast live or sold and released later, especially where fans are strongly attached to the artist. Naturally, the answer to this question is even clearer when concert activity ceases, as was the case in France for part of 2020 and 2021.

In fact, if we examine the official statements of show promoters, we see that they generally aren’t interested in tapping into the profits from concert filming. As far as they are concerned, this isn’t their core business, and they see it as competition for their main activity, or even as a gadget, one of many “goodies” given to fans to keep them happy. These assertions can be illustrated in several ways. When I was researching live music for the Département des études, de la prospective et des statistiques (DEPS — Department of Surveys, Forecasts and Statistics) for the French Ministry of Culture in the early 2010s, I had planned to interview Studio SFR, who at the time was putting on concerts that were broadcast as promotional livestreams for the telephone operator’s subscribers. Several promoters had expressed their astonishment to me, reckoning that any work on this studio was irrelevant in terms of research about live music performance because SFR was not part of the music economy (and the live performance economy in particular) but rather involved in the digital sector. Previously, the CEO of Prodiss (a federation of live music performance entrepreneurs), concert promoter Jules Frutos, considered that “gigs from your front room […] are fun the first time and can be a communication tool, but there’s no future in them. They may entertain followers a bit […] but they don’t represent a real opportunity for the reinvention of the sector. They’re just a reaction to a terrible situation. There’s no economic model or anything there” (Davet and Vulser 2020).[6] To give another example, Matthieu Drouot, one of France’s heavyweight event promoters, stated:

I don’t believe that these solutions resolve the issue. I don’t see the future of our profession in artists playing […] through video conferencing apps. I understand why people might want to watch concerts on-screen, to relive memories or as a way of passing time, but I can’t see how presenting a live concert as something other than a live concert […]. Getting together with other people is a real human need. I can’t see how we can call that into question (Aubin 2020).[7]

The pandemic has thus prompted Prodiss to publicly reaffirm the primacy of concerts at the three levels of the sector (live production and finance, organization and touring, and venues). Prodiss sees the reopening of venues as the only solution:

Live performance is the heartbeat. It is the source of revenue for many artists, backstage staff and service providers […]. This crisis has brought the interdependence of our four professions to the surface […]. Usually, different jobs have different challenges […] but during systemic crises solidarity comes to the fore. The work of broadcasters of live performance is linked to that of gig promoters, which is itself linked to venues and festivals. It’s all the same ecosystem […]. The whole chain needs to be kept in place (Moreau 2020).

In interviews that I have carried out with show promoters, they often reaffirm this argument against the filming of live performance for broadcast. One of them highlighted the fact that film teams often disrupt performances themselves, that the filming of live performances by audio-visual production teams as they try to record live content and the invasiveness of the cameras can take away from the spectacle. More broadly, it can be a source of annoyance to live performance audiences, for example by changing the scheduling of shows so that they correspond to media time slots (a bit like for sport).

Opposition from concert promoters does not primarily lie in a resistance to the modernization of companies or to a reflection on the “economic model” and the “creation of value” but is rather the result of a set of isomorphisms (Di Maggio and Powell 1983). The manner in which the sector is legally regulated is a significant variable, just as it has been during other periods for the music industry (Peterson 1990). Thus, a decisive factor in France is when the promoter of a concert filmed for broadcast, who is nonetheless the event organizer, does not have any intellectual property rights over the content and is therefore not remunerated through any revenues created from such broadcasts. After carrying out interviews with live music promoters and event organizers a few years ago, I noted that in the mid-1980s, at a time when droits voisins [neighboring rights] or other rights related to intellectual property were negotiated in France (Bouton 2015), live performances of current music were not very lucrative and were poorly structured in spite of the booming of the cultural industries. Concerts were simply promotional activities used to sell new records (Guibert 2006). Thus, those working in live performance, including representative unions, had no clout and no way of defending their right to a piece of the pie. Beyond the intellectual property rights due to song writers/composers, related rights were thus instituted for performance artists on one hand and record labels on the other. By the end of the 1990s, promoters thus sought recognition of a specific right over the recording of live performance for broadcast. In spite of public discussion at various times, in particular after the Lescure white paper in 2013 (ordered by the French Ministry of Culture) which recognized the relevance of a distinct sui generis right, they have not yet been successful.[8] We can hypothesize that if they had been, concert promoters would have had a different attitude towards filming for broadcast. For Jules Frutos, CEO of Prodiss, in the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century:

With the arrival of the internet and online TV channels, there was an enormous growth in the broadcasting of live content (live shows and concerts), to the point where they even entirely took over some themed channels […]. There was a real creation of value around the wall-to-wall broadcasting of live music which was accessible pretty much all over the internet and which wouldn’t exist without (us) gig promoters. But we don’t earn anything from this […]. It’s a question of principle and fairness [that needs to be re-established] (Frutos 2014:28). [Thus,] the performing arts are one of the rare products for which there is no return for the party who provides all the finance […]. There is a framework agreement for films of live performance made for broadcast, signed by record labels (independents and the Snep) and Prodiss, but it does not provide for any remuneration for gig promoters who therefore don’t have anything to bargain with.[9] The only right we have is that of refusing to allow cameras into venues because we are the people renting them. This is a real injustice. We started calling for related rights nine years ago, but we met with such strong opposition that we had to give up. This is where the idea of a sui generis right came in, still as something that would have to be negotiated on a case-by-case basis but that recognizes our intellectual property rights and gives us some negotiating leverage (ibid.)

For Pierre-Alexandre Vertadier from TS Prod, another promoter and a member of Prodiss:

When an artist signs with a record label, as a general rule, the label has exclusive rights over the titles recorded, including those performed live. Alongside this they also sign with a gig promoter who paradoxically does not hold any related rights, which is something that we are trying to get the Ministry of Culture to recognize […]. We mustn’t forget that there is a contractual and economic framework that means that the significant up-front investment required is provided by the promoter.[10]

In fact, the only way for event companies to get their rights recognized within the context of the increasing importance of images, filming for broadcast, and the use of livestreaming would seem to be (as part of a diversification strategy — 360 contracts) to coproduce recordings that are put on sale (and thus obtain related rights from record labels with respect to live concerts), or indeed, to manage the filming themselves and thus fulfill the roles both of concert promoter and audio-visual producer (because audio-visual producers necessarily enjoy image rights). For Frutos, however, as a show promoter, this favors companies with a more capitalistic outlook, who are involved in several activities, to the detriment of promoters operating at a lower level, for whom the creation of value ought to be recognized as such in its own right. Becoming a record label or an audio-visual producer in addition to being a concert promoter would, in this respect, amount to moving into:

something that only multinationals such as Live Nation or AEG truly manage to make a success of because they are big enough to cover the various aspects required. Small independent promoters don’t possess the skills, or even the desire, and even less so organizations that are set up to enter a field that isn’t our usual terrain. There’s no reason why our rights over images, which have become essential in terms of promotion, marketing and broadcast shouldn’t be recognized (ibid.).

Audio-visual producers and show promoters

The rise of the importance of concert filming and livestreams is not perceived in the same way by audio-visual producers who, for example, highlight the heritage dimension of filmed concerts and the fact that most concerts aren’t filmed. This is because show promoters neglect this aspect, as filming costs too much and either ticket sales or the broadcaster’s financial offer don’t remunerate them sufficiently. Sébastien Degenne, an audio-visual producer and member of the Syndicat des Producteurs Indépendants (SPI — Syndicate of Independent Producers) confirms the legally insignificant role of the show promoter in audio-visual filming of concerts, reducing their function more or less to that of a service provider: “as a general rule, in the current music sector, gig promoters simply play the role of bookers who hire out the venue, provide the sound and light equipment and employ the technicians” (Deguenne 2014:25), because, legally speaking, the record label has exclusivity over the sale of rights. This seems to make sense for image producers because “in the current music sector, the show promoter doesn’t contribute to the creation of the concert in artistic terms” (ibid.). Thus, according to audio-visual producers, “faced with the withdrawal of record companies in the financing of tours and the development of new talent, the solution lies in co-productions between gig promoters and audio-visual producers” (interview with N. Plommée from Neutra). In other words, “if we want both groups to continue to exist, co-productions are the best solution […]. The filming of concerts for broadcast is a distinct artistic object, which is located midway between two professions” (Deguenne 2014). Where concert promoters feel that the value they create isn’t recognized, audio-visual producers consider that their films constitute a work distinct from concerts once they have paid for the right to film them. French producers such as Sourdoreille or La Blogothèque have built their singularity as audio-visual producers on this particularity by conceiving the concert in terms of how they’re filmed and considering the editing and creation of videos as part of the process that they offer (Guibert et al. 2021). Seen through their perspective, the collective live performance of groups is akin to a script element. This tension can be felt between audio-visual producers and concert promoters with respect to the controversy surrounding support from the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée (CNC — National Center for Cinema and Animated Image) for the filming of concerts for broadcast, which only audio-visual producers receive.[11]

Audio-visual producers receive CNC grants for filming performances on the condition that they have obtained the authorization from the representative for the performer rights. We are predisposed to seeing gig promoters receive support too where concerts are filmed, on the condition that this grant comes from a specific sector fund financed by the Centre National de la Chanson, des Variétés et du Jazz (CNV).[12] Where concert filming is used for commercial ends, it must be considered as an extension of performance, but there’s no reason why we should be taking from Peter to pay Paul and that this grant should come from the CNC (Degenne 2014).

Naturally, the lockdown and suspension of concerts changed things since the filming of artists playing without audiences was the only activity possible. The number of opportunities to film concerts increased for audio-visual producers, just as audiences (and therefore ticketing revenue) fell to zero for show promoters, with co-productions becoming a staple (after an initial period when acoustic concerts or home concerts were directly negotiated with artists or their record labels for content that was provided to viewers free of charge).

It seems that, as we showed a few years ago, “the performing arts are suffering from the transfer of value towards the Internet” (Guibert and Sagot-Duvauroux 2013b:15). In the absence of intellectual property rights for show promoters associated with concerts that are filmed and then marketed, the sector is focusing on performance activities (the reopening of venues and festivals) and state support. This organizational approach highlights the extent to which concert promoters and audio-visual producers hold opposing positions when it comes both to livestreaming and the filming and broadcasting of concerts more generally. Promoters saw digital broadcasts as a threat and the lack of intellectual property rights as an injustice, because audio-visual producers were capturing the very value of concerts as works. By recording concerts in order to sell them to broadcasters, audio-visual producers saw concert promoters as mere service providers. This belief was strengthened by the CNC, which considered that the financial support provided had to go to audio-visual creators, songwriters, composers and performers, and not simply to those who “filmed flows” (Alexis 2019).[13]

From immersiveness to the “metaverse”

The symbolic struggle between audio-visual producers and concert promoters for legitimacy in the filming of shows, as well as the hegemony of record labels over recording catalogues (including live recordings), have not encouraged the production of livestreaming since the beginning of the twenty-first century.[14] However, demand from broadcasters and potential audiences increased during lockdown (Guibert et al. 2021). An opportunity for value creation arose during the public health crisis thanks to an increase in on-screen consumption. However, the breakdown in prior conventions came from outside or from the margins of the organizational field of live music as it was defined due to reasons both of a legal order and institutional isomorphism.

In the context of transformation of the digital production sector (Sagot-Duvauroux 2013), a branch of activity can be defined according to three components (Vaillant et al. 1984): the product, the dynamics between companies in the field (intensity of relationships, complementarity or competition), and the existence and power of professional institutions which structure the branch. We can therefore say that livestreaming is a significant driver of change because it has had an impact on all three of these parameters.

The opportunity offered by livestreams and the thesis of convergence

For some organizations involved in audio-visual production, which are sometimes producers themselves but may also simply be technical service providers, the future of concert filming (in terms of production) and livestreaming (in terms of broadcast) is wide open.[15] They highlight the fact that the more people go to concerts, the more likely they are to watch broadcast events (Idate 2014). They do not, however, see things from the standpoint of the world of live performance (whether as performance artists or as concert promoters), nor from that of audio-visual producers who seek to give “a certain perspective” to their productions of “live sessions.” These organizations rather emphasize the perspective of viewers and the emotion experienced (Déchaux 2015). The idea is that concerts generate emotional reactions, especially when they are made into an event (live or recorded at a specific time that is announced beforehand in the media), and provide the rationale for a study of the reception of broadcast concerts (Pedler 2018).[16] From this point of view, livestreaming may be an answer to offering the emotional response that can only be experienced at concerts (Vandenberg et al. 2020).

The technical case for immersion: The first issue for concert filming companies interested in livestreaming is a technical one. Indeed, the sound needs to be improved (by offering, for example, panoramic sound that changes when you move around in relation to where the stage is on-screen), or potentially adding sound generated by an audience. Questions surrounding the images are then added to this. Multicamera options may be offered, allowing viewers to choose which angle they watch the concert from, a bit like when you look from the singer to the bass player when watching a concert in-person. Cyril Zajac from Omnilive describes one possibility:

A process has been invented through which you can change your viewing angle instantaneously. And this didn’t exist before […]. There’s no interruption in the concert experience when you move from the guitarist to the singer […]. Internet users can put the show together themselves while it’s being broadcast […]. As you have access to all the viewing angles at the same time through Omnilive, you really do experience something akin to an in-person concert […]. The experiments we’re doing at the moment and the feedback we’re getting means we’re developing new tools, some of which with impacts we’re able to see now, and other technologies will appear that will transform the livestreaming experience (Astor 2020).

With the development of “immersive experiences,” a convergence between in-person and broadcast concerts has serious potential (Mama 2018).

The case for sharing events: It is possible to chat on forums and social networks about live experiences with other viewers located elsewhere in space (Bennett 2012). The survey carried out by Vanderberg, Berghman, and Schaap in 2020 shows that such interactions partially recreate the shared experience of live events (through the sharing of emojis, for example, or references to in-person parties), but only partially, because there is no bodily proximity and no immersion in the music. Looking at DJs who mix on Twitch, Warren (2020) notes a similarly lukewarm audience reaction on chats and social network messages.

The processes behind experiential marketing contribute two components that encourage convergence. First is the purchase of material objects in the form of limited-edition merchandising specially created for the event, such as livestream concerts or tour merchandise, or even the ordering of drinks (or other “goodies”) delivered to your house during the event via dedicated applications. Other “premium” elements can be added to this as part of a “360 customer” perspective, like accompanying the artist backstage (before or after the concert), having a conversation with them in private or with just a few other privileged VIPs, seeing your face come up live on-screen with a selection of other fans on a wall of screens behind the performer, or even receiving signed autographs through the post.

All these elements obviously have to be differentiated from the material experience provided to the viewer. Some people follow livestreams in a group on giant screens with a hi-fi system in a dance situation, while others watch concerts on their phones with headphones in public transportation; more qualitative studies are needed with regard to reception and types of concerts. Basing their analysis on the movements of people at the Roskilde rock festival in Denmark in 2017 and 2018, Benjamin Flesch and his collaborators have also shown that more than ten percent of the audience never went to stand in front of stages and rather stayed at the camp site for the whole event, which reflects the nuances of the festival experience and the role of performers in the provision of concerts (Flesch et al. 2018).

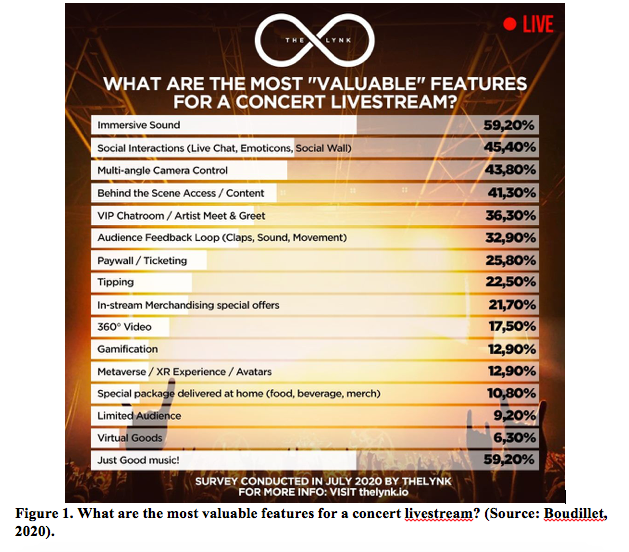

In any case, the success of several paid events during lockdowns demonstrated that it was possible to market livestream concerts in almost exactly the same way as in-person concerts.[17] It was not determined, however, whether or not this was simply an alternative associated with the restrictions of the movement of people during the pandemic. More importantly, many entrepreneurs wanted to show the potential for the monetization of broadcast concerts and, in a sense, the legitimization of livestreaming through the market. For Yvan Boudillet, from the strategic consulting firm The Lynk, rather than debating the value of livestreaming, we must first and foremost consider the user experience in order to gauge the economic potential of livestreaming. This led him to carry out a survey among 200 companies in his online professional network. According to him, immersive sound, social interactions (live chat, emoticons, social media walls), multi-angle camera control, and behind-the-scenes access/content are the most “valuable features for a concert livestream.”[18]

Once commercial potential has been demonstrated, the question of ticket sales and event organization can be examined. For Bureau Export (an organization subsidized by the French State and the musical sector whose vocation is to help in the export of French-produced artists), “the spontaneous existence of live concerts on social networks and dedicated platforms already seems to be taking shape around proposals for monetization solutions for performers and a growing number of initiatives are meeting with success among consumers” (Bureau Export Berlin 2020). However, the decisive element is that the fee-for-service system through ticket sales means that those who are selling concerts online are able to capture buyer data (Carpentier 2019).[19] This is what will lead to the concentration of sales on pay-per-view for shows that are held several days or several months in advance and not performed live. In any case, concert events made available everywhere at the same time must continue to exist. This includes the provision of forums so that fans can chat with each other and perhaps talk to performers. Paradoxically, the move towards filming of concerts ahead of the exclusive broadcast event opens the way to the reintroduction of concert venues and show promoters into the value chain. Technical professions specific to live performance are called upon so that the live concert feel can be recreated (lighting, sound, way of filming), like at the end of 2020 at venues L’Olympia and La Seine Musicale (Lutaud 2020). Moreover, it is interesting to note that big concerts with ticket sales and audiences over ten thousand people are sometimes covered as if they were concerts with live audiences and not audio-visual forms broadcast by media (ibid.).

Virtual reality and gaming

While some livestream concerts are filmed in concert venues dedicated to the organization of events, others have been filmed in sets specifically designed for livestreaming, such as castles, mountains, and forests. For example, in 2021 at “Hellfest from Home,” a festival held entirely through livestreaming (Le Gal 2021), groups played on the festival site itself, where fans had been. Indeed, livestreaming has also moved into relatively unexplored areas, such as virtual worlds. In 2020, the electronic music festival Tomorrowland held its first digital edition on the virtual island of Papilonem, where the big names of electronic music were set in 3D set designs — virtual universes — taken in particular from the world of video games (Rufat and Ter Minassian 2012).[20] During the first lockdown, on April 23rd, American rapper Travis Scott’s virtual concert took place in the video game Fortnite (Epic Games), and created a big buzz, attracting several million viewers (Potdevin 2020). Since then, many video game platforms have opened their doors to concerts, and even opened gig venues. On December 15, 2020, Rockstar Games opened a virtual club, The Music Locker, in Grand Theft Auto which hosts performing artists in residence (Singh 2020). Video games are increasingly hosting concerts from real life artists in venues they have opened virtually (Fagot 2020:20). In the same way, as it is possible to buy tools or fashion items on the Internet to dress video game characters, it is also possible to create an avatar to attend a whole host of shows, some of which have proven to be very good gigs for the artists who played them. These concerts happening in virtual worlds can be monetized. Nevertheless, the financial flows generated are still low, which is why video game producers are trying to merge their worlds to have more of an impact when it comes to big events. This is what is happening with the metaverse set up by Epic Games, which has joined forces with Nintendo, Microsoft, and Sony (ibid.).[21] Even in these examples, those involved are acting experimentally. VR concerts are distinct from concerts filmed for broadcast and immersive experiences using a multi-camera solution. In the case of VrROOM, which produced Jean Michel Jarre’s virtual concerts for the Fête de la Musique (funded by the Ministry of Culture) and New Year’s Eve in a virtual replica of Notre Dame de Paris cathedral, the concerts were broadcast live, with both Jean Michel Jarre and the audience present in the form of avatars. Regarding the Fête de la Musique concert, VrROOM’s founder Louis Cacciuttolo stated:

The reason why we wanted to do it live was so as not to lose any of the emotion of live performance and to create a true coming together with the audience […]. Jean Michel Jarre, with a VR headset over his eyes, could see his audience in the virtual world that had been specially created for the occasion, as well as the instruments he could play live with his headset […]. The artist could speak with the audience and interact with them just as in any traditional concert set-up […]. As you can imagine, creating this sort of environment is a very complex process (Cacciuttolo 2020).

In regard to interactions among audience members, he added:

It works exactly like multi-player games. People meet and talk to each other with their mics. With the VR headset, you’re in the crowd. You see the people who are beside you and you can enter into contact with them […]. The audience met up in a virtual bar after the show to carry on talking and exchanging their views on the event […]. At the Jean Michel Jarre concert the audience could also take ‘virtual drugs’ which, once they had been taken, changed the show environment, like hallucinations. It’s no doubt less dangerous than real drugs [laughs] (ibid.).

This increase in interest in virtual concerts in which participants can take on avatar profiles and get together in a virtual space, and even talk and dance, is reminiscent of what happens in e-sports, a sector which has found its audience and in which a gamer audience comes together with a sports broadcasting audience to watch virtual sport competitions (Besombes 2015). However, at least in the case of live music, there is still a lot of resistance and opposition to the gaming world of metaverses, avatars, and virtual reality. During a recent discussion on a media pure player, Jean Michel Jarre expressed his outrage over the refusal of the Avignon Festival (to which he had been invited in 2001) to take up his suggestion of investing in a virtual edition in 2020 rather than purely and simply cancelling the festival.[22] This brought the tensions between two different conceptions of the world, two irreconcilable modalities, into sharp relief (Boltanski and Thevenot 1991). It remains to be seen how livestreaming and, more generally, remote working and digital tools will impact the organizational field and production sector of live music on the margins or, on the contrary, by reconstructing the sector and branch of activity, taking account of streaming platforms, immersive technologies and virtual reality.

Conclusion

With the rise of digital peer-to-peer exchange, the increase in listening to music on streaming platforms, and the triumph of free-to-use sites such as YouTube, there has been a lot of talk about a crisis in the music economy. However, diagnosing a crisis necessitates taking into account all the parameters in play (Grenier 2011; Hesmondhalgh 2013). At the end of this research, the increasing power of live music can be observed in terms of its economic value, even though this may have seemed counter-intuitive for quite a long time, because it was seen as having a low or negligible earning potential (Baumol and Bowen 1966; Hirsch 2001).

Another aspect that we have been able to highlight is that live music has not simply seen its value increase from an economic point of view but also from a cultural one (Holt 2010). The collective and community aspect of concerts, their physical materiality and the time one has to dedicate to them (festivals in particular) has accentuated the perceived authenticity of live music. The event-creating aspects of live shows have made them a source of dramatization related to uncertainty. They are above all part of a system incorporating human beings, musicians and technicians. Concerts are always accompanied by a risk factor, including the uncertainty of natural phenomena such as the weather when concerts or festivals take place outside (Guibert 2011). Concerts, then, are by definition unique events.

The advent of the pandemic has shed light on issues that had not previously been discussed by changing concert modalities and highlighting the heterogeneity of production sectors. The performance, audio-visual, and digital economies were all nevertheless involved in the concerts, their broadcast, and the creation of value. Thus, although anticipation of a “return to normal” led all parties to engage once again in their pre-lockdown activities, the exceptional duration of lockdowns and curfews led to the development of new practices which will only partly be swept away and which herald new dynamics within the world of live music.

References

Adler, Moshe. 1985. “Stardom and talent.” American Economic Review 75(1):155–166.

Alexis, Lucie. 2019. “Culturebox, le portail culturel au cœur de la stratégie numérique de France Télévisions.” Tic&Société 13(1):159–193.

Aubin, Eddy. 2020. “Il y a une crise de confiance de la part des clients et des producteurs, qui va peut-etre redefinir la maniere dont on fait de la billetterie en france – entretien avec Matthieu Drouot.” Mgb Mag. Ma Gestion Billetterie https://www.mgbmag.fr/2020/06/17/interview-il-y-a-une-crise-de-confiance-de-la-part-des-clients-et-des-producteurs-qui-va-peut-etre-redefinir-la-maniere-dont-on-fait-de-la-billetterie-en-france-matthie/ (accessed 20 June 2021).

Bennett, Lucy, 2012. “Patterns of Listening through Social Media: Online Fan Engagement with the Live Music Experience.” Social Semiotics 22(5):545–557.

Besombes, Nicolas, 2015. “Du streaming au mainstreaming: mecanismes de médiatisation du sport électronique.” In Sports et médias, edited by Alexandre Obeuf, 179–189. Paris: CNRS Editions.

Bizet, Carine, 2019. “La mode se prend au jeu vidéo.” Le Monde, 3 December.

Boltanski, Luc and Laurent Thevenot. 1991. La justification : les économies de la grandeur. Paris: Gallimard.

Boudillet, Yvan. 2020. “What are the Most Valuable Features for a Concert Livestream?” Live music Virtual Experience https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/what-most-valuable-features-concert-livestream-yvan-boudillet/ (accessed 24 July 2020).

Bouquillion, Philippe. 1992. “Le spectacle vivant. De l’économie administrée à la marchandisation.” Sciences de la Société 26:95–105.

Bourdon, Jérôme. 1997. “Le direct: une politique de la voix ou la télévision comme promesse inaccomplie.” Réseaux 81:61–78.

Bouton, Rémi. 2015. “La loi de 85 fête ses 30 ans ! L’histoire d’un outil de filière.” Irma https://irma.asso.fr/LA-LOI-DE-85-FETE-SES30-ANS-L (accessed 20 June 2021).

Bureau Export Berlin. 2020. “Vers une structuration des pratiques de live stream.” CNM/Bureau Export. https://www.lebureauexport.fr/info/2020/04/monde-vers-une-structuration-des-pratiques-de-live-stream/ (accessed 21 July 2021).

Carpentier, Laurent. 2019. “Le big data, planche à billets du spectacle.” Le Monde, 28 January.

Davet, Stephane. 2020. “Le concert comme si vous y étiez.” Le Monde, 29 November.

Davet Stéphane. 2012. “1000 festivals, partout le même refrain?” Le Monde, 23 June.

Davet, Stéphane, and Nicole Wulser. 2020. “Des salles remplies au tiers, c’est un gouffre – entretien avec Jules Frutos.” Le Monde, 10 May.

Dechaux, Jean-Hugues. 2015. “Intégrer l’émotion à l’analyse sociologique de l’action.”, Terrains/Théories 2:1–25.

Deguenne, Sébastien. 2014. “A coproduction des captations est la meilleure solution.” Musique Info/Ecran Total 983, 12 February.

Di Maggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” American Sociological Review 48(2):147–160.

Fagot, Vincent. 2020. “Tim Sweeney, l’homme qui bouscule l’univers des jeux vidéo et les GAFA Le Monde. 20 September.” https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2020/09/20/tim-sweeney-l-homme-qui-bouscule-l-univers-des-jeux-video-et-les-gafa_6052921_3234.html.

Flesch, Benjamin, Vatrapu Ravi, Rao Mukkamala Raghava, and René Madsen. 2018. “Visualization of Crowd Trajectory, Geospatial Sets, and Audience Prediction at Roskilde Festival.” ICIS Pre-Conference Workshop Proceedings, AISeL (Association for Information Systems Electronic Library).

Fligstein, Neil. 1996. “Markets as Politics: A Political-Cultural Approach to Market Institutions.” American Sociological Review 61(4):656–673.

Grenier, Line. 2011. “Crise’ dans les industries de la musique au Québec: Ebauche d’un diagnostic.” Recherches Sociographiques 52(1):27–48.

Guibert, Gérôme. 2006. La production de la culture. Le cas des musiques amplifiées en France. Paris: IRMA/Seteun.

Guibert, Gérôme. 2011. “Local Music Scenes in France. Definitions, Stakes, Particularities.” In Stereo. Comparative perspectives on the Sociological Study of Popular Music in France and Britain, edited by Hugh Dauncey and Philip Le Guern, 223–238. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate.

Guibert, Gérôme and Philippe Eynaud. 2012. “La course à la taille dans le secteur associatif des musiques actuelles.” RECMA – Revue Internationale de l’Economie Sociale 326:71–89.

Guibert, Gérôme, and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. 2013. Musiques actuelles, ça part en live, Paris: IRMA & DEPS Ministère de la culture.

Guibert, Gérôme, and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. 2013. “Le spectacle vivant souffre du transfert de valeur vers Internet. Propos recueillis par Philippe Astor.” Musique Info/Ecran Total 944, 17 April. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=Le+spectacle+vivant+souffre+du+transfert+de+valeur+vers+Internet+guibert+sagot (accessed 20 august 2021).

Guibert, Gérôme, Franck Rebillard, and Fabrice Rochelandet. 2016. Média, culture et numérique. Approches Socio-économiques. Paris: Armand Colin.

Guibert, Gérôme, and Catherine Rudent. 2018. Made in France. Studies in Popular Music. New York: Routledge.

Guibert, Gérôme, Michaël Spanu, and Catherine Rudent. 2021. “Beyond Live Shows: Regulation and Innovation in the French Live Music Video Economy.” In Researching Live Music Gigs, Tours, Concerts and Festivals, edited by Chris Anderton and Sergio Pisfil. London: Routledge.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 2013. Why Music Matters? Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Heuguet, Guillaume. 2021. Youtube et les métamorphoses de la musique. Paris: INA.

Holt, Fabian. 2020. Everyone Loves Live Music. A Theory of Performance Institutions, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holt, Fabian. 2010. “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13(2):243–261.

Le Gal, Titouan. 2021. Effervescences collectives. Le potentiel économique et culturel de la captation de concert dans les musiques amplifiées, Mémoire de Master 2 Paris: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle.

Leveratto, Jean-Marc, Stéphanie Pourquier-Jacquin, and Raphaël Roth. 2014. “Voir et se voir : le rôle des écrans dans les festivals de musique amplifiée.” Cultures & Musées 24:23–41.

Léna, Lutaud. 2020. “Malgré de bonnes intentions, Gims rate son entrée dans l'époque du livestream.” Le Figaro. 21 December.

Mama Festival and Convention. 2018. “Streaming & Live: la grande convergence.” Paris: Le Trianon, 18 October https://live.mamafestival.com/user/event/9187.

Martin, Olivier, and Eric Dagiral. 2016. L’ordinaire d’Internet. Le web dans nos pratiques et nos relations sociales, Paris: Armand Colin.

Passeron, Jean-Claude. 1991. Le Raisonnement sociologique. L’espace non-poppérien du raisonnement naturel. Paris: Nathan.

Pedler, Emmanuel. 2018. “Un spectacle à distance? L’opéra à la télévision et au cinéma.” Enquête 13:135–151.

Peterson, Richard A. 1990. “Why in 1955? Explaining the Advent of Rock Music.” Popular Music 9(1):97–116.

Philippe-Bert, Maud. 2012 “L’heure de la stratégie globale.” Musique Info 539:18–21.

Potdevin, Pascaline, 2020. “Travis Scott sur ‘Fortnite,’ Alonzo sur ‘GTA’… Les concerts jouent le jeu du virtuel.” Le Monde Magazine. 22 June https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2020/06/22/travis-scott-sur-fortnite-alonzo-sur-gta-les-concerts-jouent-le-jeu-du-virtuel_6043664_4500055.html.

Ruffat, Samuel and Hovig Ter Missanian “Espace et jeux vidéo.” In Les jeux video comme objet de recherche, edited by Samuel Ruffat and Hovig Ter Minassian, 77–103. Paris: Questions Théoriques.

Singh, Surej. 2020. “‘GTA Online’ to Get a Virtual Nightclub with Real-World Resident DJs.” NME, 8 December https://www.nme.com/news/gaming-news/gta-online-virtual-nightclub-the-music-locker-2833912.

Vandenberg, Femke, Michaël Berghman and Julian Schaap. 2021. “The ‘Lonely Raver:’ Music Livestreams during COVID-19 as a Hotline to Collective Consciousness.” European Societies 22:141–152.

Notes

[1] I am, for example, thinking about the flows associated with the sale of tickets for events between ticketing platforms and event promoters. The procedures for the reimbursement of tickets for cancelled concerts highlighted the logistical failings of intermediaries, in particular certain ticket retailers.

[2] This recorded music can be sold in the form of replicable manufactured products or subscriptions to music streams (Guibert, Rebillard, and Rochelandet 2016).

[3] In other words, mostly generating modest sales and only sometimes, rarely, becoming blockbusters (Anderson 2006).

[4] The crucial variable used to speak about the broadcasting of the ceremony of the concert being pay-per-view (i.e. payment for access to a concert provided simultaneously to all audience members) rather than live (see below).

[5] For me one of the first wake-up calls in this respect was an interview I carried out with an artist I have known for a long time and who, before the crisis, shared his time between concert performance as a musician as part of a band and audio-visual production (filmed concerts for broadcast and music videos). While most of his musician friends saw their opportunities for touring disappear entirely during the public health crisis, it presented him with many more filmed concert opportunities, to such an extent that he wasn’t able to respond to all requests for his services. “I have never been so busy,” he told me in September 2020. However, even more than this observation, what fascinated him was the gradual transformation of the codes associated with his profession. While, before the crisis, his movements on stage where the group was playing live were marked out and restricted, they became entirely free once the audiences disappeared and this meant he was able to try out a whole new repertoire in terms of his on-camera movements.

[6] All translations of French language interviews (of concert promoters, audio-visual producers etc.) provided by myself.

[7] Managing Director of Drouot Productions

[8] In April 2014 the Inspection Générale des Affaires Culturelles (General Inspectorate of Cultural Affairs) report, Instauration d’un droit de propriété littéraire et artistique pour les producteurs de spectacle vivant (the introduction of literary and artistic intellectual property rights for performing arts promoters) (n°2014-02), considered that this was not viable, in particular because such a right would enter into competition with other existing rights (the intellectual property rights and related rights belonging to the live performer and the record label).

[9] Although the SNEP (Syndicats National de l’Edition Phonographique – the inter-professional organisation that protects the interests of the French record industry) recognised that direct negotiation with event producers was necessary, no legal guaranteed has been established.

[10] Remarks by Pierre Alexandre Vertadier, Managing Director of TS Prod, in Philippe-Bert, 2014

[11] Centre National de la Cinématographie - French Ministry of Culture agency responsible for the production and promotion of cinematic and audio-visual arts

[12] French Ministry of Culture agency responsible for the promotion of pop music and current music

[13] Which can nevertheless constitute a document with heritage value.

[14] i.e. filming for simultaneous broadcast on paid platforms or platforms financed by advertising or partnerships

[15] I’m thinking of Omnilive or the Live Music Virtual Experience group.

[16] The social network Facebook, which offers an option for publicizing “in-person” events (which users can respond to by stating that they are either “going” or are “interested”) was thus widely reappropriated during periods of lockdown or curfew and used to publicize “online” events, creating ambiguity in terms of users’ stated participation preferences.

[17] Such as concerts by M. Pokora, Jenifer, Dua Lipa, the electronic music festival Tomorrowland and the metal group Behemoth (Davet, 2020).

[18] To a lesser extent, audience feedback loops (claps, sound, movement), paywall/ticketing, tipping, in-stream-merchandise special offers, 360° video, gaming, the metaverse, special packages delivered to homes (food, beverage, merch), limited audiences, and virtual goods are also mentioned (in ‘Survey conducted in July 2020 by the Lynk’, in thelynk.io).

[19] As of 2011, Ticketmaster, the ticketing subsidiary of the events multinational Live Nation set up a Live Analytics department so as to gain a better knowledge of the behaviors of ticket purchasers (from music through to sporting events). It was thus able to state in ‘Le mariage du “ticketing” et de la data’ (the marriage of ticketing and data), Proscenium Think Tank, Prodiss, 9 March 2016, that tennis fans were more likely to go to concerts, or that Jay-Z fans were more likely to go and see a basketball match while Bruce Springsteen fans preferred hockey. See also ‘Big data et spectacle vivant, un enjeu industriel’ (Big data and the performing arts, an inter-sector challenge), Proscenium Think Tank, Prodiss, 29 January 2016.

[20] Anonymous, ‘Tommorrowland around the world. De boom à Papilionem’, DJ Mag, No. 26, July 2020, 64–69.

[21] A metaverse is a parallel digital universe that has generally been taken from the world of video games.

[22] Knowledge Immersif Forum/médiaClub debate, “Le concert se réinvente en immersive” (the reinvention of the concert as an immersive experience) with Jean-Michel Jarre, Louis Cacciuttolo and Gaspard Giroud, 8 June 2021, https://www.mediaclub.fr/evenements/retour-sur-le-grand-debat-kif-mediaclub-le-concert-se-reinvente-en-immersif-avec-jean-michel-jarre-louis-cacciuttolo-et-gaspard-giroud