In the Virtual Field: Musical Performance and the New Dynamics of Bombos in Times of COVID-19

This article is part of an ethnomusicological study focusing on the Portuguese Bombos that I have been conducting for the Doctoral Program in Music at the University of Aveiro in Portugal.[1] As I will specify, Bombos is a term that has many meanings: a percussion instrument, a set of specific musical instruments, and a collective performative practice. Despite constituting one of the “ecosystems” (Schippers and Grant 2016:340) of Portuguese traditional music spread throughout the country, studies in this field are still relatively scarce.

In fact, Bombos inhabits an epistemic space not commonly addressed by “popular music” lines of interests and themes of inquiry. Performers are not superstars, in the strictest sense; they do not record their musical repertoires, nor do they perform in any famous or celebrated Western music concert hall. Although they are paid, there are very few individuals who make their living exclusively from live performances. Such conditions do not impede the dedication these people invest in their annual activities. Especially during summer months, Bombos ensembles travel hundreds of kilometers to play in countless festivities that take place in Portugal, from north to south.

Starting in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic rendered the situation quite different this year. Due to security restrictions imposed by government authorities, musicians were prevented from meeting in person. Traditional performance spaces were abruptly silenced, and the powerful sound of those instruments that affects bodies and materialities in the open space of the street was limited to the virtual field. Operating from a logic that reflects a do-it-yourself ethos — a concept explored by Bennett and Rogers (2016), Guerra (2018), and Guerra and Quintela (2020), as I will clarify in due course — musicians during this period resorted to digital tools not part of their usual modes of performance in order to mitigate the impossibility of playing face to face. In these circumstances, the relational experience was mediated by sophisticated agents; new and vibrant forms of sociability were fostered by social distancing; and the screen became the performative space par excellence.

The pandemic also had a profound impact on my own activities. I was suddenly prevented from developing my traditional ethnography I started in late 2018. This situation has led to an imminent shift: If resorting to the virtual field seemed like a secondary task in my former practice, it now became a pressing and essential alternative, not only because it made it possible to keep in touch with my interlocutors, but because a whole new set of complex musical dynamics had started. I could not leave them out of my analysis.

This article, therefore, focuses on Bombos in the time of COVID-19. I seek to examine the new dynamics of preparation and performance, relationalities, and actions musicians undertook. For this task, I used participant observation on YouTube and Facebook groups and pages, systematically maintained a quarantine fieldwork notebook, conducted online surveys, and interviewed musicians via Zoom.

In order to situate the reader, I begin by contextualizing the term Bombos. Next, I illustrate the circumstances of my adaptation from the physical to the virtual. I document recent discussions held by scholars on alternative modalities for fieldwork and also situate specific contributions in the discipline of ethnomusicology. Describing my integration in Facebook groups, I enter the virtual field in order to present data on the impact of the pandemic. Through an ethnography of virtual practices, I then focus on three types of performance: musical videos created by musicians, the live streaming on Facebook, and the virtual sharing of pre-pandemic memories in format of texts, photographs and videos.

Bombos: typological contextualization and the ensembles’ ecological constitution

By Bombos, I am referring to three interrelated aspects:

·A percussion instrument. A bombo is a double-headed bass drum made of wood or metal sheet with heads composed of goatskin. Ranging from thirty to eighty cm. in diameter, it is held by the player with a shoulder strap and struck with one or two sticks as the player moves around.

·A set of musical instruments consisting of bombos and caixas, percussion instruments considerably smaller in size, with wire snares held under tension against the bottom head and played with two sticks. One can also find melodic instruments added to this set, such as the fife, the concertina and/or the bagpipe.

·A predominantly male, intergenerational, and collective performative practice of intense sound production and bodily movement. It is widely present in a variety of events in Portugal, such as local religious feasts and popular celebrations held in open public spaces, but also in contexts of “presentational performance” (Turino 2008:26). From the 1930s onwards, due to the cultural policies and folklorist activities enacted by the National Propaganda Secretariat during the Estado Novo, Bombos ensembles began to appear in folklore festivals.[2]

These musical groups are composed of individuals who, in addition to a common musical language, share a set of ideas about the music they make and its uses, functions, and customs. I contend that, in line with John Blacking (1995:232), they constitute “sound groups” spread across the country. According to a survey conducted by Associação Amigos do Tocá Rufar (Friends of Tocá Rufar Association), the number of ensembles currently active in Portugal exceeds three hundred.[3] As a basic unit of analysis, the idea of “sound groups” is relevant here not only because it recalls the totalizing nature of human and collectively organized sounds, but also because, as Blacking argues, it admits a greater fluidity regarding the precepts of participation in musical ensembles that transcends exclusively territorial, community, generational, or class criteria. The observations I have been conducting along with Grupo de Bombos de São Sebastião de Darque and Grupo de Bombos Regional de São Simão Os Completos, indicate that their members do not necessarily live in the same location. The age group is very diverse, with participation of children, young people and adults (from ten to sixty-five years old). Members have varied professions, working as farmers, bus drivers, mechanics, music teachers, construction workers, bank employees, nurses, lighting technicians, and waterproofing technicians. Some are also engineering and accounting students.

Each ensemble is coordinated by a leader responsible for, among other things:

· summoning members to perform;

· establishing contact with contractors and feast organizers;

· managing performance revenues and applying them to material expenses and payments to musicians;

· buying and storing musical instruments;

· driving to transport the group;

· providing the uniforms members wear; and

· managing performative dynamics and musical repertoires.

In a live performance, the number of participants is not rigidly defined, ranging from as few as seven musicians up to twenty. As a general rule, the number of bombos is never less than that of caixas or melodic instruments. The musical repertoires these ensembles play are fluid; that is, they resort to songs and percussive rhythmic patterns common to each other. As musicians indicate, the ways each group approaches them vary significantly in regards to tempo, intensity, and vigor of playing. Furthermore, repertoires are organized according to the absence or presence of melodic instruments. This circumstance is even expressed in the instrumental articulation itself: when concertinas and/or bagpipes play traditional songs such as Havemos de ir a Viana, Micas, Ramalhinho, Bareira, 13 de maio, Rosinha, or Laurindinha, bombos and caixas assume an accompaniment role subordinated to those instruments. In the absence of melodic ones, they perform compositions referred to as Pesadas.

It is precisely as part of the group when all members develop the skills to play. Collectively, musicians learn the values of participation, codes of conduct, the expressive lexicon, the musical repertoires, techniques to repair instruments, how to hold the sticks, how to tune up bombos and caixas, and the physical and mental skills essential to perform. The knowledge is transmitted orally, from the most to the least experienced players, through auditory and visual imitation processes. Although some ensembles organize rehearsals at the beginning of each year, it is precisely during live performances that specific skills are tested and improved, leading to a tremendous sense of experimentation by participants. As a matter of fact, this reveals the centrality of the practical dimension and the meaningfulness of the face-to-face shared experiences, as I had been observing through regular ethnographic incursions in the field. But, as the deliberate narrative fracture at this point of the text may suggest, my ethnographic efforts were interrupted.

On February 25th, 2020, I went into the field for the very last time before the pandemic worsened in Portugal. For the following weeks, I was supposed to continue recording in order to develop the sound ethnography project to which I was so committed. In the beginning of March, my interlocutors notified me that all performances previously scheduled were canceled. Cancellation announcements soon began to appear publicly on Facebook. On March 18th, the state of emergency decree by the Portuguese government signaled an unprecedented state of affairs. It was the beginning of quarantine, and all of a sudden everything stopped.

From the physical to the virtual field: Alternative fieldwork modalities in the pandemic and ethnomusicological responses

If it is a fact that the pandemic has violently afflicted musical ecosystems in multiple aspects, it is no less true that researchers’ tasks were drastically undermined by its constraints. I speak specifically from my own experience as a second-year doctoral student who, in the midst of an intense process of immersion in the field, abruptly found himself unable to learn from his interlocutors, to follow musical performances, to record and reflect on the sound their instruments produce. To make things worse, as far as I could remember, our classic ethnomusicology textbooks did not contain instructions on how to deal with a pandemic. Challenging more traditional procedures for the study of people making music, the situation demanded quick responses in the face of a scenario that continues to generate uncertainty.

The responses were immediately reflected in coordinated actions through communication networks at a transnational level. In the discipline of anthropology in particular, discussions on alternative methodologies for fieldwork soon started spreading. In May, the colloquium “Fieldwork in an era of Pandemia: digital (and other) alternatives” was first organized by the World Council of Anthropological Associations. Held via Zoom and broadcast on Facebook, it brought together anthropologists Clara Saraiva, Shiaki Kondo, Pamela McGrath, Rosalda Aida Hernandez, and Daniel Miller to debate the discipline’s possible responses. Three hundred people filled the virtual room in the first few minutes of the session. Although orally restricted to those speakers, the participation of the audience was nonetheless overwhelming. Typing on the platform chat, hundreds of participants interacted with each other. Posing numerous questions, students shared their anxieties and waited for answers to their dilemmas.

Though concrete answers are yet to come, scholars continued promoting discussions on tangible alternatives. Deborah Lupton’s Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic (2020), for example, consists of an open access document hosted on Google Docs. As a first stage open to collaborative edition, it presents numerous digital modalities for social research and a helpful bibliographic compilation. Geismar and Knox’s website anthrocovid.com is another meaningful effort developed at the University College London Center for Digital Anthropology. It presents ethnographic works by researchers and health professionals writing from different contexts and disciplinary fields. One of the latest issues of Social Anthropology published by the European Association of Social Anthropologists (2020) also dedicates the Forum on COVID-19 Pandemic to dozens of articles about the pandemic. Thematically diverse, these texts are not exclusively restricted to epistemological issues of fieldwork, but reflect a broader inquiry about the political, social, and economic impacts of the virus.

Although current responses of ethnomusicology seem to be more restrained compared to those of anthropology, debates on virtual fieldwork and the use of digital tools have been a component of its intellectual efforts since the beginning of the twenty-first century.[4] Suzel Reily drew attention to the growing use of the Internet and its potential as a tool for communication, teaching, learning, and disseminating research (2003). Recalling the researcher’s responsibility in what concerns ethics and usage policy, she listed initiatives and websites previously created as online repositories for music recordings, videos, scores, and ethnographic descriptions. In this piece, however, Reily does not conceptualize the Internet as a field where ethnomusicologists may integrate in order to observe, analyze, and interact with people making music.

By contrast, Abigail Wood demanded that ethnomusicologists engage in what she calls e-fieldwork (2008). Observing text messages as well as interactions in a Jewish Music email list, she argues that if the Internet is the place where people choose to carry out their musical lives, it is there that ethnomusicologists should find them. Wood nonetheless recognizes the complexity of this task due to rapid technological developments giving rise to new virtual modalities. For this reason, she stresses that “there is no one-size-fits-all paradigm for e-fieldwork” (2008:183).

Cooley, Meinze, and Syed’s 2008 piece on virtual fieldwork brings yet more reflections. As they put it, the impact of the Internet on fieldwork results from a shift in research methods driven by postcolonial theory in its attempt to investigate objects of study in diffuse time-space. Challenging the binarism expressed in the real-virtual tension, they suggest understanding communication technologies and their products as human constructions as real as any other type of cultural production. Understood as an organic part of our experience, virtuality is one of the ways in which we, as ethnomusicologists, experience people making music.

More recently, Marco Lutzu’s 2017 research on Sardinian Traditional Music groups on Facebook illustrates ethnographic efforts on this platform by analyzing the politics of sharing, the mediatization of music and its transit through multiple spaces, the processes of constructing identities, transformations in musical learning, and its impact outside virtual community. Aware of the complex challenges predicted by this literature, I then started conducting my research, from home.

In the virtual field: participant observation in the Bombos de Portugal Facebook group and the online questionnaire Bombos Pandemia COVID-19

In March 2020 I started joining discussion groups using my personal profile on Facebook. Created in 2016 and currently with around six hundred fifty members, the Facebook group Bombos de Portugal was a determining space for musical activities. By monitoring participants’ actions, it was possible to identify:

· performances broadcast “live” to an audience interacting simultaneously;

· music videos in which each member of Bombos recorded himself playing in a different time and space, resulting in a joint performance after editing processes;

· use of unconventional musical instruments due to the inaccessibility of bombos and caixas;

· the circulation of pedagogical and historical material within/between ensembles; and

· the regular sharing of memories in text, photo, audio, and video of performances that took place before the pandemic began.

In May, after noticing this virtual dynamism, I decided to circulate an online questionnaire of twenty-two questions. The Associação Amigos do Tocá Rufar provided me with their database of approximately three hundred contacts of Bombos ensembles. Presenting the document as part of my doctoral research, I tried to disseminate the access link by sending text messages to countless pages on Facebook. The message was unexpectedly considered spam, and I was therefore blocked. I then resorted to the email addresses.

Over the course of a month, I got responses from thirty-one groups across the country. I formulated closed and open questions so the musicians themselves could give complete responses. This procedure made it possible to ascertain the repercussions of the pandemic on live performances, demonstrated by the cancelation or postponement of more than seventy festivities scheduled for 2020, from the great pilgrimages of Minho region such as the Festa da Nossa Senhora da Agonia, to the famous festivities of São João de Braga and other countless festive events, to ethnographic festivals to medieval fairs, and to private events such as weddings and other social meetings.

The survey indicated that sixty-seven percent of the ensembles were not contacted by local authorities, associations or local entities in order to receive any type of support. Fifty-four percent indicated that their members did not have access to musical instruments. Regarding the use of technology, eighty-three percent listed Facebook as the main means of communication. In another question asking about measures introduced in order to mitigate COVID-19’s impact, a single value described two opposite situations: forty-eight point four percent of the groups reported not having been able to conduct any kind of activity, while another forty-eight point four percent said that “dissemination of material on social networks (videos, photos, didactic material)” was the main activity.

This duality was also noted in musicians’ words. The quotes below describe a lack of activity:

With the pandemic, music was the first activity to stop and it will be the last one to resume; I am afraid that it may have demotivated our members; It will be very complicated to resume our cultural activities; Everything has an end ... but this was not the one we all were waiting for.

Others noted efforts to meet despite the new challenges:

We have weekly meetings via Zoom to remember some work. [...] We have been creating videos so each member can demonstrate their studies and ask questions; In my opinion, this phase has also helped to develop other articulation tools that may, in future, help in a more permanent approach to the group's activities, without the need for physical presence.

Messages with a more hopeful tone were also registered, including the following ones:

To resist is to win; It will be a year of reflections, with the search for hope and calm that will be given to us after the storm passes.

In point of fact, if this questionnaire tells us a considerable amount, we must also bear in mind the absences that resonate from it. Low survey participation itself could be interpreted as significant analytical data. For one, it suggests that the impact of the pandemic may be much more severe than the collected responses indicate. I nonetheless emphasize that during this period I deliberately attempted to focus on actions musicians undertook. Demonstrating a do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos in these achievements, I want to emphasize the role individuals themselves played in this scenario. A few words are needed to contextualize this concept.

Bennett and Rogers (2016) investigated what they understood as a DIY ethos within the scope of musical production at the music scene of Brisbane. In this scenario, authors portray how the DIY ethos provides infrastructure for the perpetuation of activity in that Australian city. In Portugal, the concept has been explored in the context of the Punk scene and young subcultures emerging in a post-dictatorship period, from 1974 onwards. By analyzing the representations that participants make, Paula Guerra (2018) illustrated how the lack of infrastructure for the production and performance of Punk in the country fostered a local understanding of the DIY ethos. More recently, Guerra and Quintela (2020) have explored the expansion of fanzines and the circumstances by which they became important alternatives to conventional media. The DIY ethos portrayed in such studies reflects a process of transformation of the agents from cultural consumers to effective cultural producers. In my research, however, the idea of DIY is not imbued with the political-ideological nature so evident in Punk, nor does it correspond to the imminent transformation of consumers into producers. Rather, it compelled another transformation. Because they have been dependent on local cultural agents to play for their audiences, musicians were prompted by the pandemic to design musical activities on their own. Using social networks and digital tools, the dynamics of Bombos were outlined precisely by the actions in which musicians autonomously engaged. Such actions might also be understood as a whole set of “resilience strategies” (Titon 2015:179). In order to expose this panorama, I will present a short ethnography of three types of performance on Facebook. I intentionally bring to the text the voices of people who took part in such creations.

Edited videos, live streaming and the like as applause: an ethnography of Bombos’ virtual performances

On April 2nd, 2020, I came across a publication of a digital content that astutely put musicians physically separated in time and space into a simultaneous performance. I am referring to the musical video by the Bombos group Os Figueiras na Rua. While observing the video, I made some notes in my quarantine fieldwork notebook:

Short field note #3, April 2nd, 2020 – “Os Figueiras na Rua” on the screen: Laurindinha, unconventional percussion instruments and #stayhome

Dressed in casual attire and seated side by side, some outdoors, others indoors, fourteen musicians holding drum sticks and a set of unconventional percussion instruments appeared in a video published on Bombos de Portugal. Accompanying the melody of Laurindinha played by the concertina, a group of men and women, mostly young people, appeared onscreen with headphones connected to electronic devices they kept strictly to their ears during the two minutes and twenty seconds of performance. The texts #stayhome and “everything will be fine” joined the group’s visual identification.

Ten days later, another video was shared. By this time, even the local press reported that a “group of Bombos celebrates Easter with another theme played from home.”[5] Via Facebook, I contacted the person responsible for these publications. I then met Carlos Daniel Cerqueira, a twenty-year-old caixa player, son of Carlos Cerqueira, a bombo player in charge of this ensemble founded in 2007 in Paredes de Coura, in the north of Portugal. Carlos Daniel promptly answered my invitation for a virtual conversation. We talked extensively about the group’s history and its constitution, musical repertoires, performance contexts, and virtual activities. Speaking directly to him made it possible to understand more deeply the context and the intention of making these videos, the dynamics of preparation and communication within the group, aesthetic choices, the self-reflexivity processes regarding the acquirement of skills for editing audiovisual material, the way in which individual participation is minimized due to social distance, and the use of technology as a tool for teaching repertoires:

In early March, we started receiving all that news ... and the very first thing I did was cancel all the rehearsals. We’re approximately twenty members here, so there could be a high risk of contagion. At first, we were not aware that in the summer we would not have our feasts to play… and this idea came from a video I saw produced by a rancho folclórico.[6] I saw them on Facebook and noticed they had done a video dancing from home. And then I thought: I can also implement this here! The first thing I thought was: “we need to find out how to emulate bombos and caixas,” because the instruments by that time were all stored [at our headquarters]. And then I thought of those cans, which could sound like a caixa... and a bottle, a jerrycan, which has a sound similar to bombo. After that, I spoke to the guy who plays concertina. He recorded his video, and I recorded myself playing “caixa,” and later ‘bombo’... so I put these three videos together. I had to record myself several times before getting things done. … It’s completely different to be here, listening with headphones, and trying to emulate the same thing we usually do together, face to face. When recording we feel a little bit alone! So, I texted the group explaining I would like them to do those recordings, saying that I would like them to participate so we could virtually interact and spend time together with one another. And then I sent them the video [...] showing how it was supposed to be. I explained that they had to record with headphones so as not to keep the music in the background, this type of details. And then I did everything else... the video editing… I did it on my computer, using software. I went to YouTube to watch videos, to search information about the software… and that’s how I created that. And because of this, we ended up playing all together! I think this encouraged people to do something they weren't expecting by that time… indeed, the song you can hear in the second video was a song they had never played, neither did I. There are many ways to teach them from here. I learned it here, at home... and then I taught them. I taught them virtually, didn’t I? And they learned that virtually! But of course, there is nothing better than being all together and learning from each other. They only heard my version. If we were in a rehearsal, someone could say “how about if we play like this? so this part would get better!” People can never express themselves in the same way they do when in person, face to face. (Interview, June 4th 2020, online).

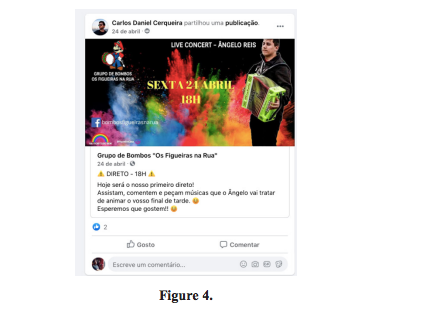

Uploaded to Facebook and YouTube, these productions have accumulated over thirty-three thousand views to date.[7] The activities of Os Figueiras na Rua at Bombos de Portugal also illustrate the sharing of live streaming, a type of performance that became a recurring practice in the following weeks:

I took part as an observer in the above-mentioned event. I wrote down in my notebook about this “live concert:”

Short field note #8, April 24th, 2020 – “I’m here to give you one hour of musical show without stopping”

Friday, late afternoon. Ângelo Reis is playing his diatonic accordion Roland FR 18 accompanied by an electronic drum in a “Live Concert.” At the end of the first song, he talks to viewers: “I’m here to give you one hour of music without stopping. Leave in the comments what you want me to play in order to make it more productive. Let’s start with Cana Verde!” Its red accordion sounds non-stop, with some pauses only to change the rhythm and tempo of the accompanying electronic drums or to read the comments. “Let’s go to the last song,” announces after approximately one hour. Ângelo recommends, then, the audience “stay at home.” Ninety comments are sent to him.

Through Carlos Daniel Cerqueira, I was able to contact Ângelo Reis. Ângelo is a nineteen-year-old man who lives in Ponte de Lima, in the north of Portugal, and plays concertina and caixa for the Bombos group Os Figueiras da Rua. Showing an intimate inclination towards digital tools, he contextualized the several live streams:

Social networks helped musicians a lot to show themselves, to work from home. Because without feasts, without anything, people get bored of not being able to show what they know. And I needed to do that. I was not playing concertina for anyone… so I opted for the Facebook live streaming in order to relieve my desire to play [...]. And because I was isolated at home — I was not going out at all, as I work in a nursing home, I was afraid of taking the virus with me — I decided to do the live streaming. As I knew everyone was at home, I knew I would have a lot of people watching. And I don’t combine anything! When I want, I take my cell phone, I take my concertina and I start it. Then, people come in and ask for songs. [...] Sometimes they even ask for songs when the streaming is over. So I take the songs they asked for, and I play them in the next streaming, so people can see that I played them. That’s why I say that, currently, my stage is my room, which is where I do my live streaming! (Interview, June 7th 2020, online).

Ângelo did not forget to stress the technical limitations with which performers must deal. Recalling a joint performance with Miguel Lavoura, he pointed out:

The sound came out with a very, very bad quality! There it is: I think Facebook was not able to handle the music, the sound of two concertinas playing at the same time. Because it is an instrument that makes a lot of noise, it has a high frequency! When we were talking to each other, the sound was spectacular. But, when playing… it failed a lot ... especially my instrument. From what the audience said in the comments, my concertina was not heard at all. And then the camera was also badly positioned, we saw one thing and it showed another. It was a very strange thing. (Interview, June 7th 2020, online).

Our conversation via Zoom finished after my interlocutor presented his recording scenario, showing the preparatory procedures and putting his concertina to sound virtually.[8] The reader can watch to that by clicking here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEF474sNdR8

Finally, I must mention another modality of performance: the memories shared on social networks. During the pandemic, I observed the regular sharing of texts, photographs and videos of live performances, informal meetings and other pre-pandemic social gatherings. Why do musicians and participants engage in such activities, and what is the meaning of this sharing? Publishing on Bombos de Portugal as well as on their personal page, the Grupo de Bombos Águias da Lage was one of those which routinely engaged in this task. “This year our group celebrates nineteen years of many stories, achievements, joys and unity. We would like to be all together to celebrate this very important date, but unfortunately it is not possible. [...] We would like, then, to recall one of our traditions, the Feast of our village, where we were supposed to debut a new musical theme!” could be read in a post presenting a musical video on July 6th, 2020. In a joint interview via Zoom, I was able to chat with Rui Fraguito, the group’s coordinator, and Renato Lameirão, a twenty-one year-old caixa player. By learning about my interlocutors’ experiences, I noticed that the act of remembering is a driving force for concatenating subjects around musical practice. Physically separated but sharing what has already been lived, the participants get closer to each other. Under the cloak of saudade — that is, the Portuguese word describing an intense sense of longing, of missing, of homesickness — sharing recognizes human presence and brings individuals together in the joint desire to resume habitual activities. I will finish by referring to Fraguito’s testimony, whose words also provide a deeper understanding of participating in such ensembles:

For me, I think it’s more about saudade. [...] To see and to review everything again. People publish on Facebook because they like what they do, and they want other people to be witnesses of what they do. Imagine: here, people in their lives will never be so, so ... how am I going to say that word? … as graced in their jobs as they are in what they do in Bombos. Of course, I’m speaking more generally ... but they will never be as applauded in life as they are in these musical groups. And people are proud of it. On the weekend, people come to Bombos. When they play, it’s to go out with friends they can’t see during the week, in order to talk a little bit, on Friday and Saturday… And then, on Sunday, we go out to the streets, to show our work and to be applauded. In other words: the applause is the justification. People miss that applause. And they like to share so other people can press the like button on their sharing. This “like” is precisely the applause they will not be able to get this year! (Interview, June 10th 2020, online).

Conclusions

In this article, I sought to document the impact of the pandemic and illustrate some dynamics of Bombos in such a scenario. Resorting to the Internet’s social networks and through digital tools, musicians engaged in new alternative modalities to perform while social distancing. Likewise, due to the constraints the pandemic has been exerting over researchers’ work, I sought to document the circumstance of my adaptation from the physical to the virtual field, the emerging discussions about this topic and to describe the work I conducted in this domain. If it is quite clear that the conditions of integration and purposes are distinct, it is no less true that the virtual, in both cases, opened up a convenient window of possibilities. I would argue that we have never been so connected via the Internet and its social networks, if that did not mean omitting an absolutely pitiful aspect: under the conditioning of economic, technological or generational aspects, the pandemic also highlighted abysmal asymmetries concerning the ability to respond to its constraints. In the case of Bombos, actions on the Internet are truly minor if we take into account the large number of ensembles in Portugal.

In this text, I tried to bring to light some minute but significant actions that were carried out by musicians. On their own, these are individuals who, in view of the absence of effective public policies which affect the entire cultural sector in Portugal, make an effective move towards keeping Bombos alive. Operating from a logic that reflects a do-it-yourself ethos, they point out their role as agents who self-reflexively search for solutions to adversities of different forms. Autonomously, they developed the necessary skills to perform: They learned how to record and edit videos, to play with unconventional instruments, to play alone in front of a camera for an audience they cannot see, to share musical knowledge virtually, and to deal with the frustrations that technologies impose on them. They also learned that remembering and sharing memories is a way to resist — that in this way the scourges inflicted by distance are at least mitigated by a breath of hope.

Due to the loosening of social distancing measures in July and August in Portugal, I was able to witness attempts by some ensembles to resume traditional performances. In one of these situations, I was invited for the first time to participate by playing the caixa. I confess that the ecstasy I felt of being there, pulsing along with my interlocutors, “feeling what it means to be part of a group of Bombos,” as they say, subsided when looking at that social scenario and its new features: masks worn by the audience did not allow for seeing their facial expressions; the safe distance maintained between people reminded all of the risk of social contact; procedures and products available for hand disinfection pointed out that things were quite unusual. At the time of writing this document (October 2020), the new decree enacted by the Portuguese government to avoid the second wave of contagion indicates nonetheless that the resumption in the physical field may take a while. If the circumstance provokes a widespread dismay, the musical dynamics depicted in this article remind us that through the action of the musicians themselves, alternative spaces and vibrant new modes of performance can be created to overcome the infeasibility of playing face to face.

References

Bennett, Andy, and Ian Rogers. 2016. Popular Music Scenes and Cultural Memory. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Blacking, John. 1995. “Music, Culture, and Experience.” In Music, Culture, and Experience – Selected Papers of John Blacking, edited by Reginald Byron, 223–242. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Castelo-Branco, Salwa El-Shawan, José Soares Neves, and Maria João Lima. 2010. “Rancho Folclórico – Enquadramento geral,” in Enciclopédia da Música em Portugal no Século XX, edited by Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, 1097–1098. Lisbon: Temas e Debates.

Cooley, Timothy, Katherine Meizel, and Nasir Syed. 2008. “Virtual Fieldwork: Three Case Studies.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives For Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory Barz and Timothy Cooley, 90–108. New York: Oxford University Press.

European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA). 2020. “Forum on Covid-19 Pandemic.” Social Anthropology – Anthropologie Sociale 28(2):211–555.

Guerra, Paula. 2018. “Raw Power: Punk, DIY and Underground Cultures as Spaces of Resistance in Contemporary Portugal.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):241–259.

Guerra, Paula, and Pedro Quintela. 2020. “Punk Fanzines in Portugal (1978–2013): A Critical Overview.” In Punk, Fanzines and DIY Cultures in a Global World - Fast, Furious and Xerox, edited by Paula Guerra and Pedro Quintela, 1–15. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lupton, Deborah. 2020. Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic (crowd-sourced document). https://docs.google.com/document/d/1clGjGABB2h2qbduTgfqribHmog9B6P0NvMgVuiHZCl8/edit?ts=5e88ae0a# (accessed 19 May 2020).

Lutzu, Marco. 2017. “Media, virtual communities, and musics of oral tradition in contemporary Sardinia.” Philomusica on-line – Rivista del Dipartimento di Musicologia e beni culturali 16(1):121–136.

Reily, Suzel. 2003. “Ethnomusicology and the Internet.” Yearbook for Traditional Music 35:187–192.

Schippers, Huib, and Catherine Grant. 2016. “Approaching Music Cultures as Ecosystems: A Dynamic Model for Understanding and Supporting Sustainability.” In Sustainable Futures for Music Cultures: An Ecological Perspective, edited by Huib Schippers and Catherine Grant, 333–351. New York: Oxford University Press.

Titon, Jeff Todd. 2015. “Sustainability, Resilience, and Adaptive Management for Applied Ethnomusicology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Applied Ethnomusicology, edited by Jeff Todd Titon and Svanibor Pettan, 157–195. New York: Oxford University Press.

Turino, Thomas. 2008. “Participatory and Presentational Performance.” In Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation, 23–65. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wood, Abigail. 2008. “E-fieldwork: a paradigm for the Twenty-first Century?” In The New (Ethno)musicologies”, edited by Henry Stobart, 170–187. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

Notes

[1] I would like to acknowledge the support of professor Dr. Maria do Rosário Pestana, professor Dr. Thomas George Caracas Garcia, David Wright, Vikki Rowland, Luísa Wink and Raquel Melo.

[2] Estado Novo refers to the Portuguese authoritarian regime, which lasted from 1933 to 1974. António de Oliveira Salazar (1933-1968) and Marcelo Caetano (1968-1974) were the dictators.

[3] This survey was conducted within the scope of the registration of Bombos in the Portuguese Intangible Cultural Heritage platform, in 2020. The research has also indicated the presence of Bombos within Portuguese immigrant communities in the USA, France, Switzerland, Australia, and Germany.

[4] Under the heading COVID-19 Resources for Ethnomusicology, the Society for Ethnomusicology announced on its website the attempt to gather relevant sources for the practice of the discipline during the pandemic. The list is concise and presents compilations organized by the American Folklore Society and the American Anthropological Association. At the time of reviewing my article for publication (05/24/2021), SEM has announced the website Musicians in America during the COVID-19 Pandemic (https://semmusicianscovid.com/about), a project with support from the National Endowment for Humanities (NEH) and Indiana University Libraries, Bloomington. Ethnomusicologists Holly Hobbs, Raquel Paraíso, and Tamar Sella conducted 240 online video interviews with a cross-section of American musicians between August and November 2020. Videos are available online along with a co-authored essay.

[5] Article published by Rádio do Minho. Available at: https://www.radiovaledominho.com/p-coura-rubiaes-grupo-bombos-festeja-pascoa-um-tema-tocado-partir-casa/.

[6] According to Castelo-Branco, Neves and Lima (2010:1097), Rancho Folclórico is a “formally organized group, consisting of dancers, singers and instrumentalists. Most Ranchos Folclóricos exhibit dances, costumes and songs understood as traditional ones, supposedly from the rural world and associated with a circumscribed geographical area: parish, municipality or former province of Portugal. The first groups emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, but it is from the 1930s that a model became institutionalized.”

[7] The link to the two videos hosted on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UC3_9lDucOM;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5Hh1_ufQnU&feature=emb_logo.

[8] In addition to Facebook, Ângelo Reis maintains a YouTube channel. His most recent project, Concertina pelo Mundo (Concertina around the World), corroborates musicians’ self-reflectivity regarding the learning of the procedures, techniques and handling of editing software. To edit his videos, he explained that he bought Filmora 9 and learned how to use it through tutorials available on YouTube.